Spanish in the USA

1. Introduction

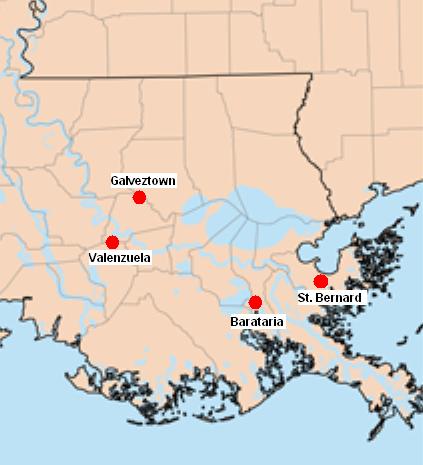

ern and northeastern cities (especially New

York City). In St. Bernard Parish (Louisiana) and in the northern New

Mexico/southern Colorado area there are small numbers of Spanish speakers who

are the descendants of the original Spanish settlers.

ern and northeastern cities (especially New

York City). In St. Bernard Parish (Louisiana) and in the northern New

Mexico/southern Colorado area there are small numbers of Spanish speakers who

are the descendants of the original Spanish settlers.

The use of Spanish in what is now the USA dates from the 16th century. A permanent Spanish settlement was established at St. Augustine in Florida in 1565 and Santa Fe in New Mexico was founded by the Spanish in 1609. By the middle of the 19th century, however, Louisiana, Florida, Texas, California, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico had all passed to US control. Louisiana was sold to the USA in 1803 by Napoleon (who had acquired it from the Spanish the previous year); Florida was ceded to the USA by Spain in 1819; Texas – now part of an independent Mexico – was annexed by the USA in 1845; and California, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico were ceded by Mexico to the USA in 1848 under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

With the exception of the archaic

variety that persists in New Mexico/Colorado and also the isleño dialect

of St Bernard Parish, the Spanish spoken in the USA does not represent a direct

continuation from colonial times. Rather, it is the consequence of large-scale

19th and 20th century immigration, above all from Mexico, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Mexican varieties of Spanish (also known as Chicano Spanish) are

found in the border area from southern California to Texas, Cuban varieties in

the Florida peninsula and Puerto Rican varieties in the big northeastern cities

such as New York. Such ‘transplanted’ Spanish will in many cases also have

undergone processes relating to language contact and bilingualism.

2. General Features of US Spanish

Given the varying origins of most Spanish speakers in the USA, the main generalizations that can be made about US Spanish concern recurrent bilingual phenomena, principally relating to interference from English. Ramírez (1992:184–90) identifies cases such as the following.

First, the gerund may be used where standard

Spanish calls for an infinitive, as in the sentence below:

(1) El

dinero que gana lo gasta en tomando.

In addition, determiners may be

omitted where none appear in the corresponding English construction. Thus

standard Spanish versions of (2) and (3) below would have a quantifier (e.g. unos

or algunos) before niños and the appropriate form of the definite

article before religión:

(2) Niños vinieron.

(3) Religión es algo importante.

Another recurrent phenomenon is the

insertion of a before an infinitival complement in imitation of English to:

(4) Querían a comenzar.

The normal indirect object construction that is used with body parts – as in Me lavo las manos ‘I wash my hands’ – is often replaced by an English-style configuration involving a possessive determiner, as in (5)

Derived Form

|

Source

|

parquear |

park |

chequear |

check |

dostear |

dust |

dumpear |

dump |

chipear |

ship |

trostear |

trust |

friquearse |

freak out |

chapear |

sharpen |

below:

(5) Lavo mis manos.

The integration into Spanish of

English words is widespread. The main morphological process involves applying

the suffix -ear to a Hispanized form of the English source word, as illustrated in the table to the right.

Finally, Spanish lexical items

undergo semantic shift under the influence of cognate or formally similar English

words or through the contextually inappropriate use of partial translation

equivalents. Thus carpeta ‘wallet’, for example, comes to mean ‘carpet’, grosería ‘rudeness’ comes to mean ‘grocery’, children may be said to atender

a la escuela (= asistir a la escuela ‘to attend school’) and

candidates might correr para alcalde (= presentarse para alcalde ‘to

run for mayor’).

3. New Mexico/Colorado

In contrast to most other areas of the

USA, northern New Mexico/southern Colorado still harbours communities of

speakers whose Spanish is a direct continuation of the language spoken by the

colonial settlers, albeit a dialect that has undergone some modification under

the influence of Mexican Spanish and also English. Given that New Mexico was a

peripheral area during the colonial period, the local Spanish exhibits many of

the usual non-standard innovations and, as a consequence, has more in common

with Central American Spanish than with neighbouring Mexican Spanish. From the

point of view of phonetics and phonology, the main distinguishing features are

the following:

Debuccalization of /x/, as in [ˈmehiko] México.

No sound corresponding to orthographic ll, as in [ˈsia] silla ‘chair’, [kaˈβeo] cabello ‘hair’, [aˈnio] anillo ‘ring’.

Paragoge of [e] after final [l] or [ɾ], as in [isaˈβele] Isabel, [koˈmeɾe] comer ‘to eat’.

In terms of the lexicon, although

some New Mexican dialectal items persist, such as molacho ‘toothless’ and calihero ‘index finger’, the bulk of the vocabulary bears a Mexican

imprint (e.g. cachetazo ‘slap’, mancuernilla ‘twin’, chueco

‘knock-kneed’), implying a number of Nahuatl loanwords (e.g. chapo

‘short’, huaraches ‘sandals’).

4. St. Bernard Parish

Some Spanish settlement of Louisiana

took place during the brief period (1763–1803) when the territory was under

Spanish control. At the end of the 1780s just over 2,000 Canary Islanders

established themselves in the area around New Orleans. Some of their descendants,

located mainly in St. Bernard Parish, still speak a variety of Spanish that is

a direct continuation of the speech of the 18th century Canary Island settlers;

hence the application of the name isleño to both the dialect and its

speakers.

At the end of the 1780s just over 2,000 Canary Islanders

established themselves in the area around New Orleans. Some of their descendants,

located mainly in St. Bernard Parish, still speak a variety of Spanish that is

a direct continuation of the speech of the 18th century Canary Island settlers;

hence the application of the name isleño to both the dialect and its

speakers.

Isleño speech exhibits clear affinities with

Caribbean and Canary Spanish. For example, syllable-final /s/-weakening is

routine, as are phenomena relating to syllable-final liquids ([l] to [ɾ] modification and vice-versa,

elision and assimilation) and the velarization of word-final /n/. Ch-lenition

is not uncommon either.

The isolation of the community until

the 1940s has ensured the survival of many of the vulgarisms and archaisms that

are typical of such groups. Metathesis, for example, is evident in [ˈmaɾðe] madre ‘mother’ and [ehˈtoɣamo] estómago ‘stomach’,

while /b, d/ to [g] modification is apparent in [teɣuˈɾon] tiburón ‘shark’ and [ˈpjeðɾa] piedra ‘stone’. Archaism

is prevalent in the morphology, with the common use of such obsolete forms

(i.e. obsolete in the standard language) as haiga and vaiga (pres.

subj. of hacer and ir), truje and vide (pret.

of traer and ver) and semos (pres. ind. of ser).

Other recurrent morphological

phenomena include the application of diminutive suffixes directly to noun or adjective

roots, as in lechita ‘milk’ and dulcito ‘sweet’ (compare standard

lechecita and dulcecito); the use of -nos as

the 2nd person plural marker in verb endings, as in estábanos ‘we were’; and

stress shifts from verb ending to root, as in vénganos instead of vengamos.

These phenomena are all well-documented in Canary Island Spanish.

The Canary heritage is apparent also

in the use of non-inverted wh-interrogatives and the para + NP +

infinitive construction:

(6) ¿Por qué usted llora?

(7) Para un niño nacer, tenían partera.

It is in the lexicon, however, that

the Canary origins of the dialect are most noticeable. The following items, for

example, are typical of the Canary Islands and are also found in isleño Spanish:

andoriña ‘swallow’, enchumbarse ‘to get wet’, fecha ‘bolt’ (these three are ultimately of Portuguese origin), botarete ‘extravagant

person’, despechar ‘to wean’, mancar ‘to wound’, nombrete

‘nickname’, virar ‘to turn’, vuelta de carnero ‘somersault’, cambao

‘bent’, cascarón ‘crust (of bread)’, enamorar ‘to court’, guirre

‘vulture’, quemar ‘to be sore’, gago ‘who stammers’, taramela

‘doorstop’.

In addition to items of Canary

origin, the isleño dialect exhibits English and French loanwords, some

of the latter stemming from the Cajun variety. Anglicisms include farmero

‘farmer’, marqueta ‘market’, siper ‘zip’, guachimán

‘watchman’, spring ‘mattress’ and suiche ‘switch’. Gallicisms

include robiné ‘tap’, brasié ‘bra’, garmansé ‘crockery

sideboard’, sosón ‘sock’, surito ‘small mouse’, tablié

‘apron’, pití lorié ‘bay leaf’, pañé ‘cesto’. Borrowings from

Cajun include (ar)ranchá ‘to prepare’, creón ‘chalk’, prería

‘medow’, politisián ‘politician’, bayul ‘branch of a river’.

References

Ramírez, Arnulfo G. 1992. El español de los Estados Unidos, el lenguaje de los hispanos. Madrid: Mapfre.