|

Articles by subject: Topics: The World Bank and the IMF |

||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

BIG dams are horrible things. They flood wide areas, drowning wildlife and displacing thousands of people. That is why the World Bank loves to fund them. Continuing its quest to destroy the planet after which it is named, this sinister organisation decided to lend money to Uganda to erect a concrete monstrosity on the Nile. Ugandan environmentalists were outraged, according to the International Rivers Network (IRN), a pressure group in Berkeley, California. Sebastian Mallaby, a columnist for the Washington Post who was at The Economist until 1999, went to Uganda to investigate.

He asked the IRN to put him in touch with the Ugandan environmentalists who were so outraged. The IRN refused, for some reason. Undeterred, he tracked down the Ugandan group that the Californians were working with. It had 25 members—“not exactly a broad platform from which to oppose electricity for millions,” Mr Mallaby observes. And the people who were to be displaced? The author found them uniformly happy with the compensation offered. The only gripes he heard were from those outside the area that was to be flooded, who were angry that they would not share in the bonanza.

Pressure groups like the IRN spoon-feed lazier journalists than Mr Mallaby. Unelected, unaccountable non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are generally assumed to be honest and virtuous. The World Bank, which does more to fight poverty than any other public body, is generally viewed as the villain. This is partly because it makes mistakes, but mostly because it is besieged by single-issue fanatics in the West who condemn it whenever it fails to make their issue its top priority.

James Wolfensohn, the World Bank's president since 1995, has made strenuous efforts to accommodate the NGO swarm. Every infrastructure project the Bank funds must meet rich-world standards: nothing pretty may be bulldozed unless strictly necessary, and no worker may be asked to do anything that a Californian might find demeaning. As a result, fewer dams, roads and flood barriers are built in poor countries. More poor people stay poor, live in darkness and die younger.

| |

| |

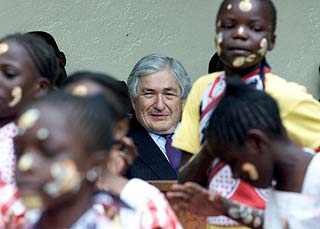

Wolfensohn among clients |

“The World's Banker” sets out to be a biography of Mr Wolfensohn, but it is really as much about the rich world's relations with the poor. Mr Mallaby writes about this vast topic with vigour and wit, and in a tone so reasonable it makes you want to slap the people who scale office blocks to unfurl banners proclaiming that the “World Bank Approves China's Genocide in Tibet”. (An absurd claim about the Bank, as Mr Mallaby painstakingly documents, and an unhelpful—to Tibetans—exaggeration of China's policy.)

Another reason why the Bank is unpopular is that it promises too much. An organisation that lends only a few billion dollars a year is hardly in a position to end global poverty. Its greatest value is intellectual: its staff form the brightest concentration of development specialists anywhere. Its research into the slippery question of how poor countries can grow prosperous is always more comprehensive, and sometimes more brilliant, than anything else on offer. When it lends, other lenders heed the signal.

Though not an original thinker, Mr Wolfensohn has generally been on the right side of most of the important debates. He embraced the idea of debt relief while it was still taboo in Washington, and his awesome charm and networking skills helped make it happen. He was also the first World Bank president to acknowledge that corruption in poor countries is not a minor blemish, but one of the main reasons why they remain poor.

His triumphs outnumber his errors, but the errors matter. Trying to placate the Bank's critics seemed a good idea at the time, and he has managed to build constructive relationships with the more grown-up NGOs, such as Oxfam. Yet most pressure groups “do not have an ‘off' switch,” as Mr Mallaby puts it. Nothing the Bank does will ever satisfy them, but by attaching some of the conditions that they demand to its loans, the World Bank makes those loans unattractive, despite their cheapness, to the more creditworthy developing countries, such as Brazil, South Africa and China.

If the Bank were to lose its healthier clients, that would affect its own financial soundness, and therefore its ability to help the poorest. Mr Mallaby writes: “Rather than trying to rebuild the Bank's relationship with all three categories of stakeholder—shareholders, NGOs and borrowers—Wolfensohn should have been more sensitive to the trade-offs between them. And he should have put the borrowers' interests a clear first.”

Mr Wolfensohn comes across as filled with “a roaring restless hunger to do all the things that man can do, and to succeed at all of them.” On the negative side, he is so vain that he prefers to shout at his subordinates than share credit with them. He probably won't like this book. But anyone else who cares about development will.

The World's Banker: A Story of Failed States, Financial Crises and the Wealth and Poverty of Nations.|

Copyright © 2004 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights reserved. |