FOOD SECURITY AND GLOBAL FOOD MARKETS

There

is a major global concern about whether or not we are about to

experience a Malthusian disaster - as a consequence of human demands

for food (a function of population and income) outrunning global

capacities to produce and provide food. For example:

UK Foresight report on Global Food and Farming Futures (The Future of Food & Farming, 2011) "The global food system will experience an unprecedented confluence of pressures over the next 40 years. On the demand side, global population size will increase from nearly seven billion today to eight billion by 2030, and probably to over nine billion by 2050; many people are likely to be wealthier, creating demand for a more varied, high-quality diet requiring additional resources to produce. On the production side, competition for land, water and energy will intensify, while the effects of climate change will become increasingly apparent.The need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to a changing climate will become imperative. Over this period globalisation will continue, exposing the food system to novel economic and political pressures."

Any one of these pressures (‘drivers of change’) would present substantial challenges to food security; together they constitute a major threat that requires a strategic reappraisal of how the world is fed. Overall, the Project has identified and analysed five key challenges for the future. Addressing these in a pragmatic way that promotes resilience to shocks and future uncertainties will be vital if major stresses to the food system are to be anticipated and managed.The five challenges, outlined further in Sections 4 – 8, are:

A. Balancing future demand and supply sustainably – to ensure that food supplies are affordable.

B. Ensuring that there is adequate stability in food supplies – and protecting the most vulnerable from the volatility that does occur.

C. Achieving global access to food and ending hunger.This recognises that producing enough food in the world so that everyone can potentially be fed is not the same thing as ensuring food security for all.

D. Managing the contribution of the food system to the mitigation of climate change.

E. Maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services while feeding the world."

"In view of the current failings in the food system and the considerable challenges ahead, this Report argues for decisive action that needs to take place now."

Economist Intelligence Unit: Global Food Security Index. & relationship with Womens' Economic Opportunities.

FAO's Data Visualiser page. FAO's Food Price Index (since 1990)

But - consider how much progress has been made in the last half-century:

In 1960, the world’s population reached 3 billion, and was still growing without apparent limit. Paul Ehrlich, 1968, predicted that rapid population growth would lead to increased famines and “a substantial increase in the world death rate” (p xi). The Club of Rome declared in 1972 that “If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years” (Meadows et al. 1972, p. 23). The Malthusian proposition that food demands, growing exponentially both with population and income growth, would necessarily exceed food supplies, which appear only to grow arithmetically, seemed probable, if not inevitable. Yet in the last 50 years, world population has more than doubled, growing by an additional 4 billion people, but the number of world’s starving has not increased, albeit still remaining obscenely large. Chen and Ravallion, 2012, “find evidence of a continuing decline in the incidence of absolute poverty in the developing world. The overall percentage of the population living below $1.25 a day in 2008 was 22%, as compared to 52% in 1981. We find that 1.3 billion people in 2008 lived below $1.25 a day, as compared to 1.9 billion in 1981. Progress has been uneven across regions, but (encouragingly) all regions have seen falling poverty counts in the 2000s” (p 22). The FAO, 2011, reports that the proportion of undernourished people in developing countries fell from 33% in 1969/71 to less than 20% in the first decade of this century.

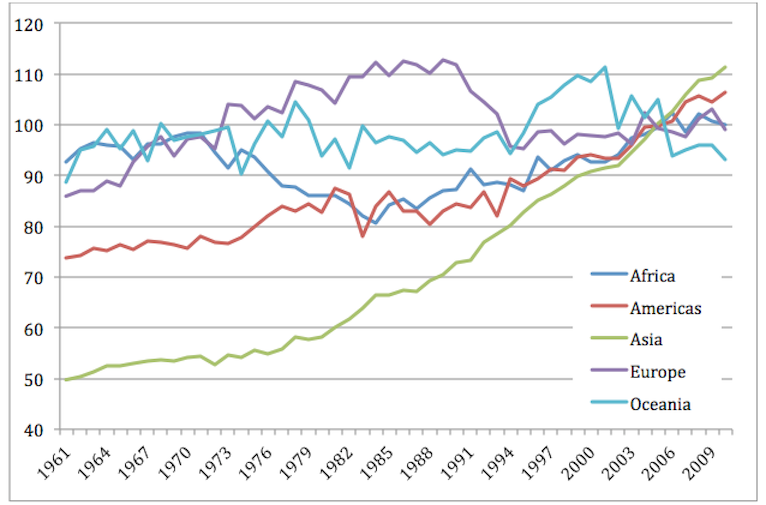

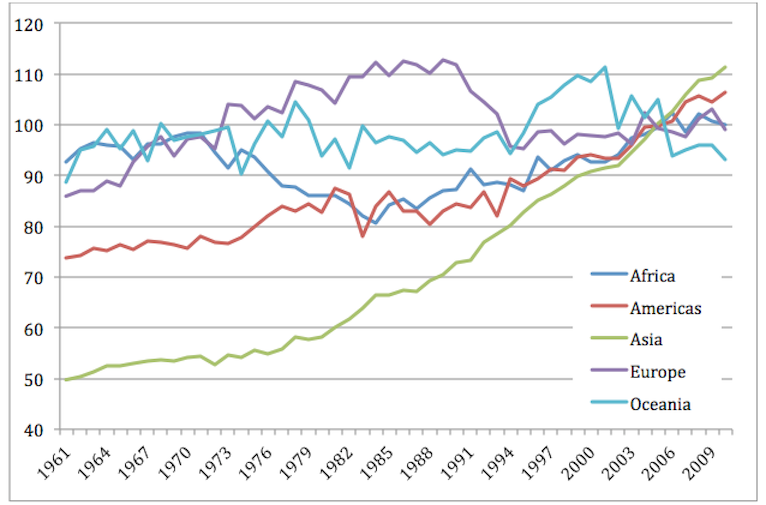

Despite the dire predictions about the world’s capacity to cope with 7 billion people fifty years ago, we appear to have managed pretty well, without subjecting increasing numbers of people to starvation or malnutrition (though present levels of malnutrition and chronic food shortage are by no means acceptable). Our net food production per head has generally increased (Figure 1) and the prices of food have not (so far) shown any substantial tendency to increase – as they will when our global self-sufficiency comes under more serious threat, which perhaps they have already begun to signal (Figure 3)

Refs:

Chen, S. and M. Ravallion, 2012, “More Relatively-Poor People in a Less Absolutely-Poor World.” Policy Research Working Paper 6114. Washington D.C.: World Bank

FAO, 2011, The State of Food Insecurity in the World, 2011 edition, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers and W.E. Behrens III. 1972, The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Book.

Figure 1: FAO Per capita Net Production Index (source: FAO Stat)

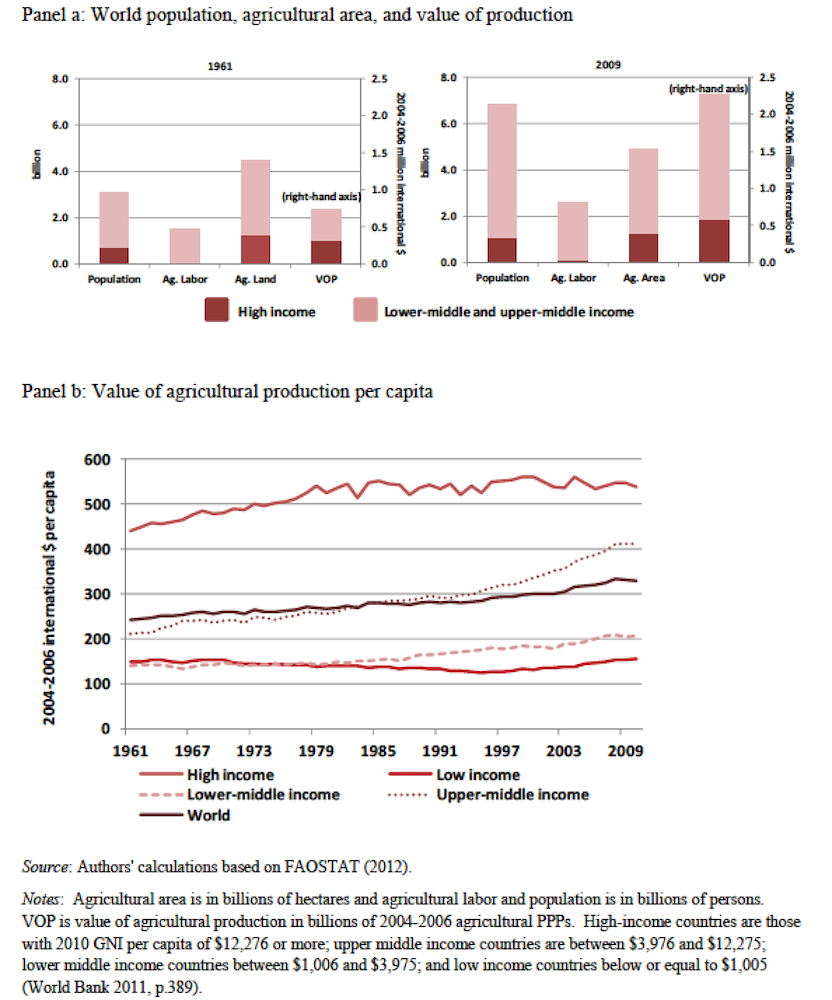

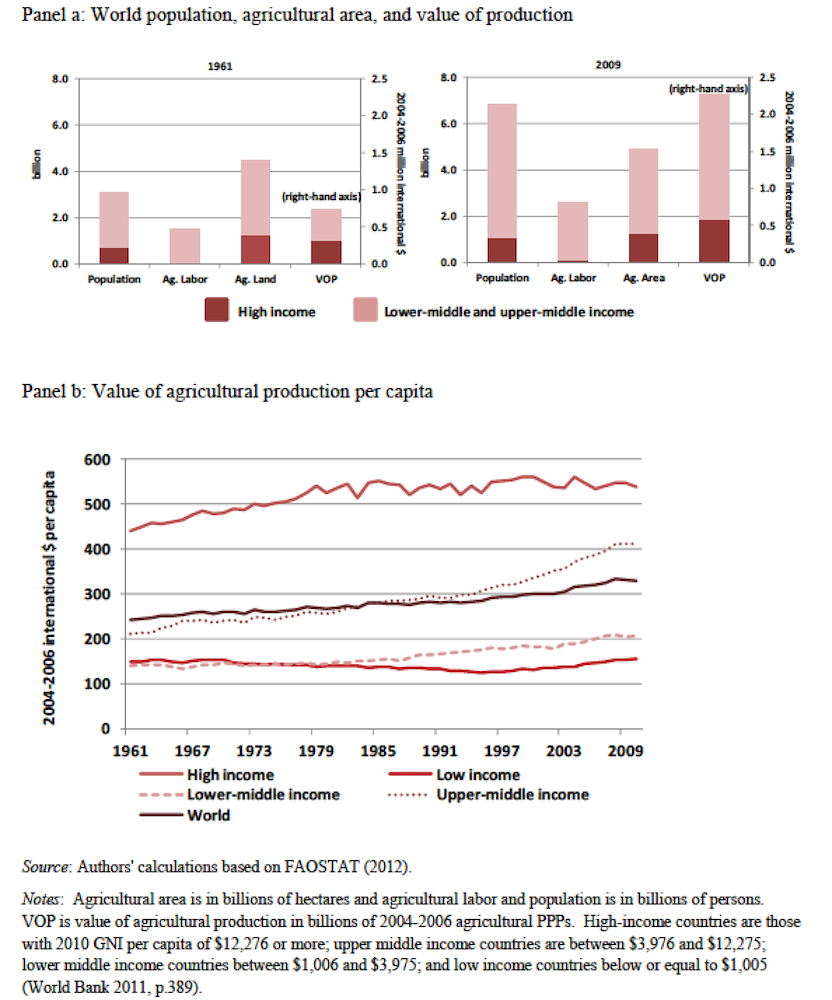

Figure 2: World population, agricultural output and land in agriculture, 1960 and 2009 (Source: Pardey et al., 2012)

Figure 3: FAO Food Price Index (real terms) 1961 - 2010 (Source: FAO HLPE report, 2011 on Price Volatility and Food Security)

We have managed to increase the value of food production per head of the population, with most of this increase happening in the upper middle income countries (Figure 2b above). However, food production per capita remains stubbornly static. This impressive global performance has been associated with a substantial shift in global production, exemplified by wheat. In 1961/3, Russia accounted for 15% of global wheat production and was the world’s largest producer, but by 2008/10, Russia only accounted for just over 8% of global production, with India and China together accounting for almost 29% (up from 12% in 1961/3).

The capacity of the planet (and the people on it) to provide enough food for all in the future depends on our capacities to:

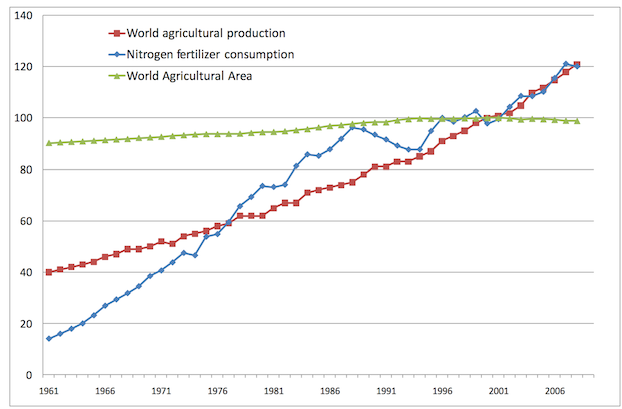

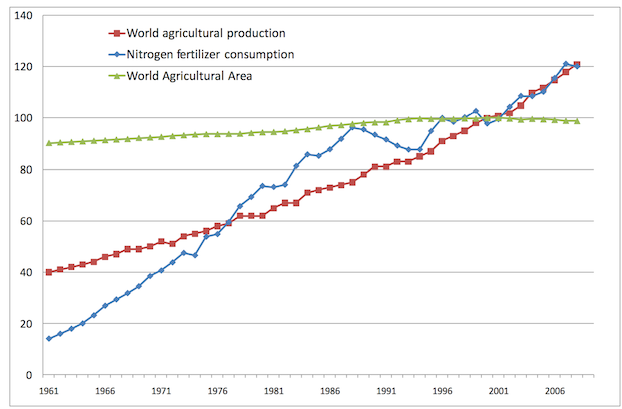

See above and Change in Global Crop land (1961 - 2008) (From FAO's SOLAW - State of the World's Land & Water Resources for Food & Agriculture - summary report, site includes some interactive maps & Notes/comments on the main maps.) We have, effectively, grown our extra food 'out of the fertiliser bag':

Source: FAO HLPE, 2011, p. 34.

Bruinsma (ibid) projects that only 9% of future output increases (to 2050) will need to come from extensification, reflecting increasing constraints on further cultivation and relying instead of further yield improvements. Although much of irrigated agriculture around the world, and much of developed country agriculture (including Brazil) show rather small yield gaps, the gaps remain very substantial (of the order of 50%) in rain fed agriculture, in much of Africa and still in much of Eastern Europe. If these gaps could be closed, at least some analysts conclude that we can feed another 2bn with present technologies, and with present cultivated land areas. As Godfrey et al., 2010, note “Substantially more food, as well as the income to purchase food, could be produced with current crops and livestock if methods were found to close the yield gaps” (p 813)

Refs:

Hertel, T., 2011, “The Global Supply and Demand for Agricultural Land in 2050: A perfect storm in the making?”, Am. J. Agr. Econ.,93 (2), 259 – 275

Godfray, H C J, Beddington, J R, Crute, Ian R, Haddad, L, Lawrence, D, Muir, J F, Pretty, J, Robinson, S, Thomas, S M and Toulmin, C (2011), Science 327 , 812 – 18, DOI: 10.1126/science.1185383

Meeting the challenge of providing enough, for all, forever, requires more than simply generating the capacities and capabilities of supplying food. It also requires adaptation and innovations in what we consume, and in our abilities to generate sustainable incomes to nourish both our capacities and to continually recreate worthwhile livelihoods. Aside from the impressive growth in global food production over the past half century, a major factor in the reduction of relative food insecurity has been the growth in incomes – providing the previously poor with the wherewithal to purchase food (among many other things). Economic growth is therefore seen as a necessary requirement for both food and livelihood security, and will lead inevitably to both greater demands on our increasingly scarce land resources (for cities and infrastructure) as well as to substantial changes in diets and associated food requirements. In addition, as fossil fuels become relatively more expensive (both because of the increasing costs of finding and mining existing reserves, and because of the reflection of environmental costs and GHG emissions in the cost of their use), so the use of biofuels will become more attractive, further potentially increasing the demands on our scarce land until or unless third generation biofuels and other sustainable energy sources become viable.

See Fuglie and Wang, (USDA, ERS, 2012). New Evidence Points to Robust But Uneven Productivity Growth in Global Agriculture

See, also, FAO HLPE report on Food Security & Climate Change, June, 2012.

Other important data: OECD/FAO Agricultural Outlook, 2012 - 2021. (Summary) and FAO's Statistical Yearbook, 2012 - Food and Agriculture (or here, as an alternative entry point), and also, the FAO's State of Food and Agriculture (annual).

And Canwefeedtheworld.org.

See, also Jo Swinnen on The Right Price of Food (May 2010) - see: "Only a few years ago the widely shared view was that low food prices were a curse to developing countries and the poor. The dramatic increase of food prices in 2006-2008 appears to have fundamentally altered this view. The vast majority of analyses and reports in 2008 and 2009 state that high food prices have a devastating effect on developing countries and the world’s poor. This reversal of opinion raises questions about the old and the new arguments and about the proposed remedies. It also raises questions about the causes of this dramatic turnaround in analysis and policy conclusions. In this paper I document these changes in perspective and I discuss potential implications and offer hypotheses on the cause of the change in views." & also a more recent analysis of self-reported food insecurity during the 2008 food price crisis: Verporten et al, 2012, LICOS discussion paper 303.

UK Foresight report on Global Food and Farming Futures (The Future of Food & Farming, 2011) "The global food system will experience an unprecedented confluence of pressures over the next 40 years. On the demand side, global population size will increase from nearly seven billion today to eight billion by 2030, and probably to over nine billion by 2050; many people are likely to be wealthier, creating demand for a more varied, high-quality diet requiring additional resources to produce. On the production side, competition for land, water and energy will intensify, while the effects of climate change will become increasingly apparent.The need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to a changing climate will become imperative. Over this period globalisation will continue, exposing the food system to novel economic and political pressures."

Any one of these pressures (‘drivers of change’) would present substantial challenges to food security; together they constitute a major threat that requires a strategic reappraisal of how the world is fed. Overall, the Project has identified and analysed five key challenges for the future. Addressing these in a pragmatic way that promotes resilience to shocks and future uncertainties will be vital if major stresses to the food system are to be anticipated and managed.The five challenges, outlined further in Sections 4 – 8, are:

A. Balancing future demand and supply sustainably – to ensure that food supplies are affordable.

B. Ensuring that there is adequate stability in food supplies – and protecting the most vulnerable from the volatility that does occur.

C. Achieving global access to food and ending hunger.This recognises that producing enough food in the world so that everyone can potentially be fed is not the same thing as ensuring food security for all.

D. Managing the contribution of the food system to the mitigation of climate change.

E. Maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services while feeding the world."

"In view of the current failings in the food system and the considerable challenges ahead, this Report argues for decisive action that needs to take place now."

Economist Intelligence Unit: Global Food Security Index. & relationship with Womens' Economic Opportunities.

FAO's Data Visualiser page. FAO's Food Price Index (since 1990)

But - consider how much progress has been made in the last half-century:

In 1960, the world’s population reached 3 billion, and was still growing without apparent limit. Paul Ehrlich, 1968, predicted that rapid population growth would lead to increased famines and “a substantial increase in the world death rate” (p xi). The Club of Rome declared in 1972 that “If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years” (Meadows et al. 1972, p. 23). The Malthusian proposition that food demands, growing exponentially both with population and income growth, would necessarily exceed food supplies, which appear only to grow arithmetically, seemed probable, if not inevitable. Yet in the last 50 years, world population has more than doubled, growing by an additional 4 billion people, but the number of world’s starving has not increased, albeit still remaining obscenely large. Chen and Ravallion, 2012, “find evidence of a continuing decline in the incidence of absolute poverty in the developing world. The overall percentage of the population living below $1.25 a day in 2008 was 22%, as compared to 52% in 1981. We find that 1.3 billion people in 2008 lived below $1.25 a day, as compared to 1.9 billion in 1981. Progress has been uneven across regions, but (encouragingly) all regions have seen falling poverty counts in the 2000s” (p 22). The FAO, 2011, reports that the proportion of undernourished people in developing countries fell from 33% in 1969/71 to less than 20% in the first decade of this century.

Despite the dire predictions about the world’s capacity to cope with 7 billion people fifty years ago, we appear to have managed pretty well, without subjecting increasing numbers of people to starvation or malnutrition (though present levels of malnutrition and chronic food shortage are by no means acceptable). Our net food production per head has generally increased (Figure 1) and the prices of food have not (so far) shown any substantial tendency to increase – as they will when our global self-sufficiency comes under more serious threat, which perhaps they have already begun to signal (Figure 3)

Refs:

Chen, S. and M. Ravallion, 2012, “More Relatively-Poor People in a Less Absolutely-Poor World.” Policy Research Working Paper 6114. Washington D.C.: World Bank

FAO, 2011, The State of Food Insecurity in the World, 2011 edition, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers and W.E. Behrens III. 1972, The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Book.

Figure 1: FAO Per capita Net Production Index (source: FAO Stat)

Figure 2: World population, agricultural output and land in agriculture, 1960 and 2009 (Source: Pardey et al., 2012)

Figure 3: FAO Food Price Index (real terms) 1961 - 2010 (Source: FAO HLPE report, 2011 on Price Volatility and Food Security)

We have managed to increase the value of food production per head of the population, with most of this increase happening in the upper middle income countries (Figure 2b above). However, food production per capita remains stubbornly static. This impressive global performance has been associated with a substantial shift in global production, exemplified by wheat. In 1961/3, Russia accounted for 15% of global wheat production and was the world’s largest producer, but by 2008/10, Russia only accounted for just over 8% of global production, with India and China together accounting for almost 29% (up from 12% in 1961/3).

The capacity of the planet (and the people on it) to provide enough food for all in the future depends on our capacities to:

- expand the areas under cultivation (extensification);

- increase the yields on presently cultivated land (intensification), either through direct increase in crop (and livestock) yields, or through cropping intensity (multiple cropping); & through both increasing yields through new varieties and production practices, and closing present 'yield gaps' between potential yields and actual yields.

- changes in food (fibre, feed and biofuel) consumption mix.

See above and Change in Global Crop land (1961 - 2008) (From FAO's SOLAW - State of the World's Land & Water Resources for Food & Agriculture - summary report, site includes some interactive maps & Notes/comments on the main maps.) We have, effectively, grown our extra food 'out of the fertiliser bag':

Source: FAO HLPE, 2011, p. 34.

Bruinsma (ibid) projects that only 9% of future output increases (to 2050) will need to come from extensification, reflecting increasing constraints on further cultivation and relying instead of further yield improvements. Although much of irrigated agriculture around the world, and much of developed country agriculture (including Brazil) show rather small yield gaps, the gaps remain very substantial (of the order of 50%) in rain fed agriculture, in much of Africa and still in much of Eastern Europe. If these gaps could be closed, at least some analysts conclude that we can feed another 2bn with present technologies, and with present cultivated land areas. As Godfrey et al., 2010, note “Substantially more food, as well as the income to purchase food, could be produced with current crops and livestock if methods were found to close the yield gaps” (p 813)

Refs:

Hertel, T., 2011, “The Global Supply and Demand for Agricultural Land in 2050: A perfect storm in the making?”, Am. J. Agr. Econ.,93 (2), 259 – 275

Godfray, H C J, Beddington, J R, Crute, Ian R, Haddad, L, Lawrence, D, Muir, J F, Pretty, J, Robinson, S, Thomas, S M and Toulmin, C (2011), Science 327 , 812 – 18, DOI: 10.1126/science.1185383

Meeting the challenge of providing enough, for all, forever, requires more than simply generating the capacities and capabilities of supplying food. It also requires adaptation and innovations in what we consume, and in our abilities to generate sustainable incomes to nourish both our capacities and to continually recreate worthwhile livelihoods. Aside from the impressive growth in global food production over the past half century, a major factor in the reduction of relative food insecurity has been the growth in incomes – providing the previously poor with the wherewithal to purchase food (among many other things). Economic growth is therefore seen as a necessary requirement for both food and livelihood security, and will lead inevitably to both greater demands on our increasingly scarce land resources (for cities and infrastructure) as well as to substantial changes in diets and associated food requirements. In addition, as fossil fuels become relatively more expensive (both because of the increasing costs of finding and mining existing reserves, and because of the reflection of environmental costs and GHG emissions in the cost of their use), so the use of biofuels will become more attractive, further potentially increasing the demands on our scarce land until or unless third generation biofuels and other sustainable energy sources become viable.

See Fuglie and Wang, (USDA, ERS, 2012). New Evidence Points to Robust But Uneven Productivity Growth in Global Agriculture

See, also, FAO HLPE report on Food Security & Climate Change, June, 2012.

Other important data: OECD/FAO Agricultural Outlook, 2012 - 2021. (Summary) and FAO's Statistical Yearbook, 2012 - Food and Agriculture (or here, as an alternative entry point), and also, the FAO's State of Food and Agriculture (annual).

And Canwefeedtheworld.org.

See, also Jo Swinnen on The Right Price of Food (May 2010) - see: "Only a few years ago the widely shared view was that low food prices were a curse to developing countries and the poor. The dramatic increase of food prices in 2006-2008 appears to have fundamentally altered this view. The vast majority of analyses and reports in 2008 and 2009 state that high food prices have a devastating effect on developing countries and the world’s poor. This reversal of opinion raises questions about the old and the new arguments and about the proposed remedies. It also raises questions about the causes of this dramatic turnaround in analysis and policy conclusions. In this paper I document these changes in perspective and I discuss potential implications and offer hypotheses on the cause of the change in views." & also a more recent analysis of self-reported food insecurity during the 2008 food price crisis: Verporten et al, 2012, LICOS discussion paper 303.

ENVIRONMENTAL FOOTPRINTS & CONSEQUENCES

Ecological Footprints by Country (Economist, May 2012) & the data from The Global Footprint Network. & the Ecological Footprint Atlas, 2010

Who cares and does something about it? - The Greendex Score and Guilt (Economist) and the National Geographic Survey data "Consumer Choice and the Environment—A Worldwide Tracking Survey” measures consumer behavior in areas relating to housing, transportation, food, and consumer goods. Greendex 2012 ranks average consumers in 17 countries according to the environmental impact of their consumption patterns and is the only survey of its kind.

Meanwhile, GHG emissions continue to rise, while the international community seems unwilling to commit to any serious reduction (Doha, 2012), while a recent Chatham House report (2012) on global resource futures, and associated graphics pages (Resources Futures), are worth a visit, and follow their links - e.g. international investment in (agricultural) land (Land Portal Info), and IFPRI's report on the 'land rush'.

Who cares and does something about it? - The Greendex Score and Guilt (Economist) and the National Geographic Survey data "Consumer Choice and the Environment—A Worldwide Tracking Survey” measures consumer behavior in areas relating to housing, transportation, food, and consumer goods. Greendex 2012 ranks average consumers in 17 countries according to the environmental impact of their consumption patterns and is the only survey of its kind.

Meanwhile, GHG emissions continue to rise, while the international community seems unwilling to commit to any serious reduction (Doha, 2012), while a recent Chatham House report (2012) on global resource futures, and associated graphics pages (Resources Futures), are worth a visit, and follow their links - e.g. international investment in (agricultural) land (Land Portal Info), and IFPRI's report on the 'land rush'.