1. Etymology

2. Clitic placement in Old Spanish

2.1 Main clauses3. Transition to the modern system

2.2 Finite subordinate clauses

2.3 Infinitival clauses

1. Etymology

The Spanish clitic pronouns are the weak object pronouns me, te, lo(s), la(s), le(s), nos and os (previously vos), together with reflexive se. Of these, the items with first- or second-person reference, together with reflexive se, descend from the corresponding accusative forms of the Latin personal pronoun:

mē > me

tē > te

nōs > nos

vōs > vos > os

sē > se

Latin had no bespoke non-reflexive personal pronoun in the third-person category, and instead used its demonstrative pronouns for this purpose. In the variety from which Spanish later emerged, usage must have converged on the distal demonstrative ĭlle ‘that one’, as it is from accusative and dative forms of this item that the Spanish third-person object pronouns descend, as is shown in Table 1 below.

|

Direct object

|

Indirect object

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | ||

| Singular | ĭllum > lo | ĭllam > la | ĭllī > le |

| Plural | ĭllōs > los | ĭllās > las | ĭllīs > les |

Neither the forms of the Latin personal pronoun nor those of the demonstrative ĭlle were originally clitics, i.e. linguistic expressions lacking prosodic independence and needing to attach phonologically to an adjacent word. Self-evidently, however, these items must have evolved into clitics when they occurred as the direct or indirect object of the verb. As part of this process, the relevant forms of ĭlle also underwent apheresis of their initial syllable: (ĭl)lum > lo, (ĭl)lam > la etc.

An additional point to note is that, when immediately followed by ĭllum, ĭllam, ĭllōs or ĭllās, as in e.g. ĭllī ĭllum dedit ‘he/she gave it to him/her’, the singular dative form ĭllī gives ge rather than le in Old Spanish. This is due to the final vowel of ĭllī evolving into the semivowel [j] before the initial /e/ (= ĭ) of the following pronoun, so that, for example, ĭllī ĭllum became [ljelo] once apheresis of ĭllī’s initial syllable had occurred. The sequence [lj] developed regularly to /ʒ/ in Old Spanish, whence the form ge, pronounced /ʒe/. With the devoicing of the sibilants, this latter pronunciation gave way to /ʃe/, whereupon ge was amended to se, by analogy with the reflexive pronoun se (< sē). The overall development is shown below, using ‘†’ to indicate an analogical form:

ĭllī ĭllum > gelo > †se lo

ĭllī ĭllam > gela > †se la

ĭllī ĭllōs > gelos > †se los

ĭllī ĭllās > gelas > †se las

In this use, se is functionally equivalent to either le or les, depending on the context. For example, se lo di can mean either ‘I gave it to him/her’ or ‘I gave it to them’. The same was true of Old Spanish ge, implying that at some point in the pre-Old Spanish period, the singular dative pronoun ĭllī displaced its plural counterpart ĭllīs in this particular context. Had this not occurred, the final /s/ of ĭllīs would have blocked any semivocalization of the ī in its final syllable and, as a consequence, its reflex before lo, la etc. would be les, as it is in all other contexts.

2. Clitic placement in Old Spanish

The placement of object pronouns in Classical Latin gives little indication of what was to follow in Old Romance. In the example below, from Cicero, the pronoun me appears sentence-initially and is separated from its verb adduxerunt by three syntactic constituents, viz. the subject tuae litterae, the negative adverb numquam and the prepositional complement in tantam spem. On both counts, its placement would infringe the constraints that governed the positioning of weak object pronouns in the medieval Romance languages.

Me tuae litterae numquam in tantam spem adduxerunt quantam aliorum;

‘Your letters never brought me into as much hope as did those of others’

(Cic. Att. 3.19.2)

In later Latin, or more generally in spoken Latin, it is possible that a tendency emerged whereby object pronouns that were not pragmatically salient, for example as foci or as contrastive topics, were positioned immediately after the first element in the sentence, excluding any sentence-initial peripheral elements, such as hanging topics or certain types of temporal or locative adverbial (cf. Salvi 2011: 363). If so, this tendency must have been progressively consolidated, as it is manifested rather more clearly by the weak object pronouns of Old Spanish and indeed of Old Romance generally.

2.1 Main clauses

In Old Spanish there was a fundamental distinction between main clauses and finite subordinate clauses as regards the linearization or placement of clitic pronouns. While proclisis (immediate preverbal placement of the clitic) was the rule in finite subordinate clauses, weak pronouns in main clauses were often enclitic on the verb (i.e. the finite verb). Enclisis was in fact obligatory whenever the clitic would otherwise be sentence-initial, as in (1) below.

The prohibition on sentence-initial clitics in Old Spanish—and in Old Romance more generally—is known as the Tobler-Mussafia law, a principle widely discussed in the syntactic literature. In its conventional formulation, however, the Tobler-Mussafia law is too weak: although enclisis was indeed obligatory when the clitic would otherwise occupy sentence-initial position, it was not confined to such contexts. In fact, enclisis was frequently found even when proclitic placement would not have resulted in a sentence-initial clitic (see examples (7) to (9) below).

This is because certain types of preverbal element were invisible to the clitic linearization algorithm. That is, even though their presence would have prevented the clitic from being sentence-initial had it appeared preverbally, the clitic was still placed after the verb. To understand the distinction between elements that were invisible for purposes of clitic placement and those that were not, it is helpful to begin with the latter group—namely, the class of elements that attracted proclisis.

The most consistent proclisis attractor was the negation marker no(n), whose presence invariably triggered preverbal clitic placement in main clauses, as shown in (2):

In the same way, objects and prepositional complements, together with certain types of adverb, that were moved from a postverbal position to a preverbal one (i.e. before the finite verb) also triggered obligatory proclisis. In (3) to (5) below, the item which has been moved from its usual postverbal position is underlined (and both it and the proclitic weak pronoun are in bold font):

Note that the structure in (3) is distinct from the common modern structure known as clitic left dislocation, in which a sentence-initial phrase is resumed by a co-referential clitic. In (3), the object esta alcaria is not resumed by a clitic (or by anything else); it has simply been moved from its usual postverbal position to a preverbal one, an operation which is now quite rare but by no means impossible. Interestingly, while object fronting as in (3) triggered obligatory proclisis in Old Spanish, clitic left dislocation, which was much less common than in the modern language, usually correlated with enclisis, as in the example below (for further discussion, see Mackenzie 2019: 35).

The common feature of proclisis attractors in Old Spanish is that they are elements which are highly integrated into clause structure: items like the negation marker, along with objects and other complements, are the basic syntactic building blocks of any language. In contrast, the elements that were ‘invisible’ for clitic linearization were syntactically peripheral—that is, less tightly integrated into clause structure. This category includes items such as naturally preverbal locative or temporal adverbials, sentence-initial topics, and the like—elements that can usually (though not always) be separated from the rest of the clause by an intonation break.

In the example below, the adverbial phrase otro dia is a peripheral element of the relevant kind. That is, it is not part of the clause’s core syntax, which is reflected in the fact that a pause can naturally be inserted after it. As a consequence, it is invisible for clitic linearization purposes, and the weak pronoun le appears after the verb enuiaron, exactly as it would if nothing preceded the verb:

Similarly, in (8) below, the preverbal conditional clause is peripheral to the core syntax. The following finite verb faze then appears before its clitic rather than after it. Notice that the scribe seems to have sensed the syntactic separateness of the conditional clause, as he inserted a semicolon immediately after it—a punctuation mark which in medieval manuscripts often indicates an intonational break:

An interesting case is that of the preverbal subject, which has a variable effect on clitic linearization in Old Spanish. Frequently, this element co-occurred with enclisis, implying that it was structurally peripheral:

On the other hand, it also occurred commonly with proclisis, suggesting full integration within clause structure:

The variation seen in (9) and (10) may be linked to the fact that Old Spanish—like modern Spanish—was a null subject language, implying that the true syntactic subject was often an unpronounced subject pronoun rather than an overt linguistic element. If that was the case in (9), then the preverbal phrase ell Emperador would not be the true syntactic subject, but rather a left-peripheral topic resumed by an unpronounced subject pronoun—i.e. the meaning would be: ‘And the emperor, he received it...’. Under that analysis, enclisis would be expected. The assumption in (10), by contrast, would be that the apparent subject is the true syntactic subject and not a left-peripheral topic, with proclisis following accordingly. For a more detailed discussion, including quantitative data, on clitic linearization with preverbal subjects in Old Spanish, see Mackenzie 2019 (pp. 87–89 and p. 95).

Summing up the discussion so far, the restriction on the medieval clitic pronoun in finite main clauses (beyond the requirement that it be linearly adjacent to the finite verb) was essentially that it could not be the first element in the core of the clause—i.e. excluding peripheral items such as sentence-initial topics, framing adverbials and the like. There is, however, no general agreement as to why this was the case. One plausible conjecture is that the syntax-driven pattern of clitic placement observable in the high Middle Ages was a residue of an earlier stage in the language’s evolution—late spoken Latin, say, or pre-literary Spanish—during which weak pronouns were, by hypothesis, inherently enclitic or ‘left-leaning’. On this view, they originally had to attach phonologically to a host expression (not necessarily the verb) to their left. Over time, this constraint lost its phonological basis, but the requirement for a word or phrase to the clitic’s left persisted, reinterpreted in syntactic terms—with phonological attachment being replaced by structural proximity.

The conjunction et, y, e, &

Many clauses in the Old Spanish manuscripts are introduced by et, y, e, or &, all meaning ‘and’. When such clauses are not part of a larger subordinate clause, they behave just like independent sentences with respect to clitic linearization, although the coordinating conjunction itself is invisible to the linearization algorithm. This invisibility arises from the fact that words meaning ‘and’ are coordinating conjunctions, meaning they are syntactically external to the constituents they link. As a result, enclisis was mandatory (at least initially) in main clauses where proclisis would have placed the clitic directly after et, y, e, or &:

Note that in (12) the first clause also exhibits enclisis, specifically of the clitic cluster se le, with the se component reduced to s and orthographically attached to the verb torno. In this case, however, enclisis is not due to adjacency to &; rather, it is because the preverbal phrase al tercero dia is a peripheral element, just like otro dia in example (7), and thus invisible to the linearization algorithm.

2.2 Finite subordinate clauses

In contrast to main clauses, finite embedded or subordinate clauses in Old Spanish display systematic proclisis from the earliest attested texts, indicating that the basic pattern of clitic linearization in these contexts has remained stable over time. Example (13) below offers a typical illustration:

For additional examples, see the embedded que-clauses in (1) and (2), as well as the preverbal si-clause in (8).

Note that the requirement for proclisis in subordinate clauses overrides the general rule that clitics do not follow et, y, e, or &. Thus in (14) below, la appears proclitically with touiere despite following et, because the entire coordinate clause is embedded within a larger subordinate clause—namely, the conditional clause si fuere negro et la touiere alguno consigo:

As regards infinitival clauses introduced by a preposition, Old Spanish exhibited variation between proclitic and enclitic placement of the weak pronoun. This is illustrated in the following two examples:

In infinitival clauses governed by clause-union verbs, the clear tendency in Old Spanish was for the clitic to appear immediately before the finite verb, as in (17), rather than attaching enclitically to the infinitive (as is common in Modern Spanish):

An additional possibility was for the clitic to occur between the finite and non-finite verbs, as in (18):

Note that in the type of case illustrated by (18), the weak pronoun should be analysed as enclitic on the finite verb rather than proclitic on the infinitive. This conclusion is supported by the near-total absence of the ‘clitic-medial’ pattern in Old Spanish when the finite verb is preceded by a categorical proclisis trigger such as negation (see Mackenzie 2019: 77–78). If medial clitics were capable of being true proclitics on the infinitive, we would expect more such cases even in the presence of negation—but this is not what the data show.

3. Transition to the modern system

In modern Spanish, enclisis on a finite verb is only possible in (non-negative) imperative clauses. Conversely, clitics can now freely occur in sentence-initial position, as illustrated below:

Weak pronouns in Spanish have therefore undergone a fundamental transformation. The old Tobler-Mussafia clitic, whose placement was variable and conditioned by syntactic structure, has been replaced in all finite contexts (except positive imperatives) by a form that behaves as inherently proclitic.

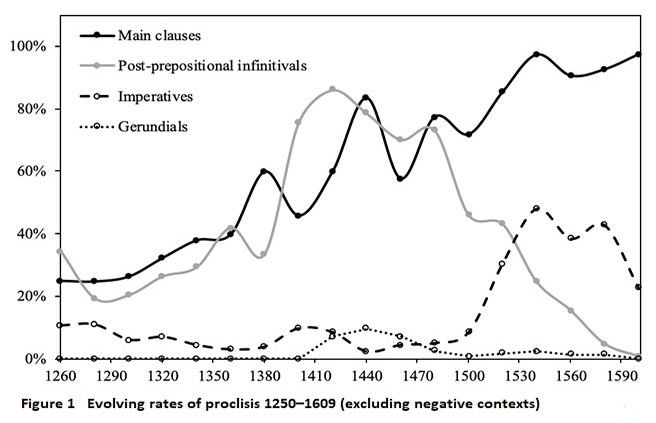

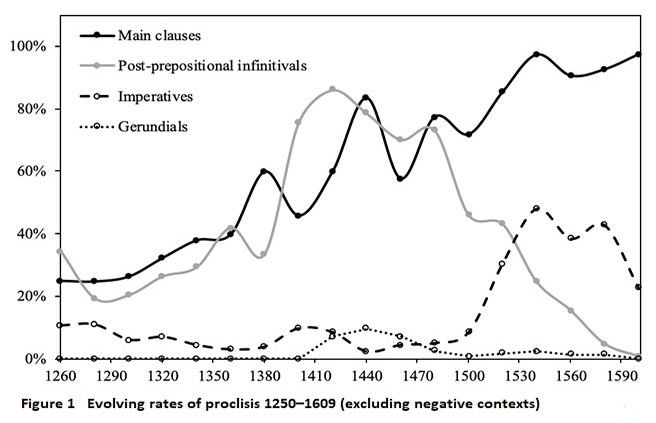

This transformation was largely complete by the early seventeenth century, as indicated by the unbroken black line in Figure 1 below (from Mackenzie 2019: 92):

In infinitival clauses, two major developments have taken place. First, proclisis has been completely lost. In the specific context of infinitival clauses following a preposition (cf. (15)), the trajectory of this change is especially striking: usage shifted markedly in one direction during the late Middle Ages, and then reversed in the early modern period. As the unbroken grey line in the figure above shows, proclisis increased in this context from around the 1270s until the 1430s, after which it declined rapidly and had virtually disappeared by the start of the seventeenth century. For detailed discussion of this and other clitic-related ‘failed changes’, see Mackenzie 2019: 97–108.

The second major development has been the increasing frequency of enclisis on the infinitival component of clause union structures (see Davies 1997). This trend has occurred at the expense of both the pattern illustrated in (17) and the now-obsolete pattern in (18), the latter of which disappeared entirely in declarative and interrogative contexts. The loss of this medial placement pattern should be viewed as a direct consequence of the loss of enclisis in finite clauses (aside from imperatives), since medial placement in clause union contexts entails finite enclisis, not infinitival proclisis.

4. References

Davies, Mark. 1997. ‘The evolution of Spanish clitic climbing: a corpus-based approach.’ Studia Neophilologica, 69, 2: 251–263.

Fontana, Josep M. 1993. Phrase structure and the syntax of clitics in the history of Spanish. PhD dissertation. University of Pennsylvania.

Mackenzie, Ian. 2019. Language structure, variation and change: the case of Old Spanish syntax. Palgrave Macmillan / Springer Nature.

Poole, Geoffrey. 2013. ‘Interpolation, verb-second, and the low left periphery in old spanish.’ Iberia 5, 1:69–98.

Rivero, María Luisa. 1991. ‘Clitic and NP climbing in Old Spanish.’ In H. Campos and F. Martínez-Gil (eds), Current Studies in Spanish Linguistics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 241–82.

———— 1993. ‘Long Head Movement versus V2, and null subjects in Old Romance.’ Lingua 89: 217–45.

Salvi, Giampalo. 2011. ‘Morphosyntactic persistence.’ In The Cambridge history of the Romance Languages Vol. 1, eds Martin Maiden, John Charles Smith and Adam Ledgeway (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 318–81.