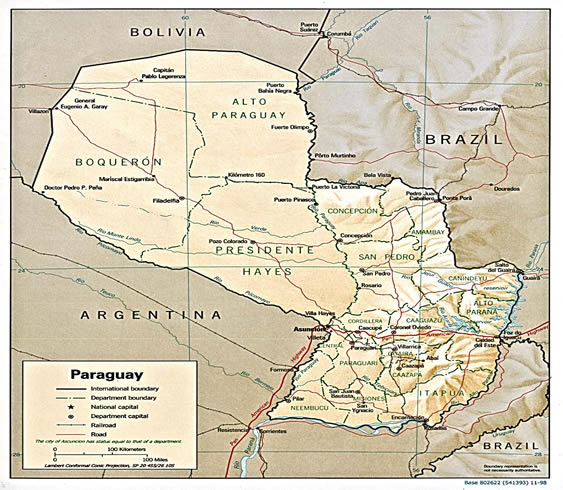

In 1776 Paraguay was made part of the Viceroyalty of La Plata (together with Argentina, Bolivia, and Uruguay) but unity with Buenos Aires was always superficial. After gaining its independence from Spain in 1811, Paraguay endured the isolationist dictatorship of José Rodriguez de Francia (1819-1840), which resulted in much of country’s cultural apparatus being dismantled. The rest of Paraguay‘s history is, if anything, bleaker still. Some 90% of the male population died in the devastating War of the Triple Alliance (1865-1870), which involved Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Paraguay was involved in another major war in the 1930s, this time with Bolivia over control of the Gran Chaco. And from the Chaco War until almost the end of the 20th century, Paraguay was under almost continuous military dictatorship.

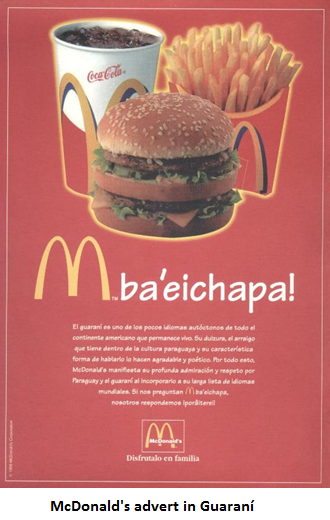

One of the interesting aspects of Paraguayan social history is the frequency

of mixed unions during the colonial period. Men greatly outnumbered women among

European settlers, especially in the remote areas to the southeast of Bolivia, and an obvious solution to the problem was interethnic

marriage. For much of the colonial era, then, the prototypical Paraguayan family

consisted of a Spanish-speaking father and a Guaraní-speaking mother, a fact

that may partly explain the widespread Spanish-Guaraní bilingualism that exists

today in Paraguay. Among bilinguals, there is normally a preference for Guaraní

in intimate, personal and familiar situations. Moreover, Guaraní is used more

in rural than in urban areas. Thus in Asunción and other large towns,

approximately 30% of the population habitually uses Spanish at home, about 20%

prefers Guaraní and about 50% alternates between the two. In rural areas, only

about 2% of the population prefers Spanish, 75% prefers Guaraní and the

remainder alternate between the two.

Although Spanish as spoken by the Paraguayan middle and upper classes is not

very different from the speech encountered in the rest of the Southern Cone,

interference from Guaraní is frequently encountered at the lower end of the

socioeconomic spectrum, particularly in eastern Paraguay (between the Paraguay

and the Paraná rivers) and also in adjacent areas in Argentina (the provinces

of Formosa, Misiones and Chaco, together with parts of Corrientes).

2. Phonetics and phonology

Like the Andean region, the Paraguay area is one of the few parts of the

Spanish-speaking world in which the /ʎ/ ~ /ʝ/ distinction has any vitality.

Indeed, the pronunciation ofthe digraph ll as [ʎ] is almost a badge of national identity for many Paraguayans. The reason for the

retention of /ʎ/ is not easy to

determine, however. It used to be regarded as an instance of Guaraní influence,

although that language does not appear to have the phoneme in its inventory. A

more plausible explanation is that /ʎ/-retention

is simply an archaism, simultaneously reflecting the large number of Spaniards

from northern Spain who colonized the region and the country’s persistent

cultural isolation.

Like the rest of the Southern Cone, Paraguay is a syllable-final

/s/-weakening area, although speakers will gravitate towards [s] in formal

situations. Out-and-out elision or assimilation to a following consonant is

common only among speakers from the lower socio-economic strata.

Assibilation of [ɾ] is also common, but usually only after [t], as in [ˈtʂipa] tripa ‘gut/innards’ and [ˈpotʂo] potro ‘colt’.

Turning now to cases of possible Guaraní influence, a striking feature in certain Spanish varieties in Paraguay is the frequent insertion of a glottal stop at word boundaries, particularly when the second word begins with a vowel, as in [aˈβlaɾʔespaˈɲol] hablar español ‘to speak Spanish’. The geographical distribution of this feature coincides almost exactly with the distribution of Guaraní-speaking areas, viz. Paraguay, northeastern Argentina and eastern Bolivia. Moreover, an identical feature has long been identified in the Guaraní language itself.

Another salient feature that could well be due to substratum influence is the affrication of intervocalic /ʝ/, as in [ˈmadʒo] mayo ‘May’ and [ˈledʒes] leyes ‘laws’. Guaraní has a voiced palatal phoneme that is also normally pronounced as an affricate. Like the insertion of a glottal stop at word boundaries, affrication of /ʝ/ is a feature that is encountered both in the Spanish of Paraguay and in that of the Guaraní-influenced areas of northeastern Argentina.

In particular, a transfer has occurred of certain evidential particles. Guaraní has a set of modal particles that indicate the status of what is being said or talked about: personally vouched for by the speaker, derived from an indirect source, inexact or fictitious. Several of these seem to have been transferred wholesale into Guaraní-influenced dialects of Spanish, where they are placed in clause-final or postverbal position. The following examples are from Granda 1994 (pp. 138-9), although it must be stressed that Granda’s examples are themselves taken from literary works that attempt to capture vernacular speech patterns (in Granda’s view they are accurate reproductions).

In the first place, voí expresses a strong degree of commitment to a proposition:

(1) [. . .] pero eso pelotazo que venía de arriba, ¡mamó picó! Con eso no había caso voí . . .

‘but those shots that came from high up, boy! With those I didn’t stand a chance’

The particle ndayé has a reportative function, in that it is used when the information conveyed comes from an indirect source, such as a reported utterance:

(2) Y

eso, según me cuenta mi hijo Manolo, que etudia ciencia contaule, se llama ndayé ‘sociedá de consumo’.

‘And that, according to my son Manolo, who studies accounting, is called the consumer society.’

Nungá has what Granda (1994:139) calls an ‘approximative’ function. It acts as a hedging device:

(3) [. . .] vino una vieja que e visitadora nungá y le dice que lo mitaí

tiene que hacer lo que quiere.

‘An old lady came who apparently is a social worker and she says to her that children have to do what they want.’

Other particles - viz. gua’ú, ko, nikó, nió, katú - have been borrowed into Spanish, although they have a less easily identifiable function. Gua’ú (where the apostrophe indicates a glottal stop) is said by some to indicate the falsity of a proposition, while the remaining four seem to appear in neutral assertions (in Granda’s terms (p. 138), they ‘indican la certeza objetiva de la información transmitida’ [‘indicate the objective truth of the information conveyed’]).

Terms of address represent an additional area of interference. Guaraní-dominant Paraguayans do not always master the differences between vos/tú and usted, since Guaraní has no distinction between deferential and non-deferential terms of address.

Other non-standard grammatical phenomena are quite salient, although a link with Guaraní is not as easy to demonstrate as in the preceding cases. One of the most striking of these is the use of de + disjunctive pronoun in contexts where other Spanish dialects would employ an indirect object clitic:

(4) Se

perdió de mí mi chequera. (Cf. standard Seme perdió la chequera.)

‘I lost my cheque book.’

(5) La

madre cuida a su hijo para que no se ahogue de ella. (Cf. standard ... para que no se le ahogue.)

‘The mother looks after her child so that he doesn’t get overwhelmed.’

As in other areas with a strong indigenous presence, vernacular speech in both Paraguay and northeastern Argentina exhibits null definite direct objects, as in (6):

(6) Llevé los papeles para la famarcia y no sé si perdí.

‘I took the papers for the chemist and I don’t know if lost [them].’

Finally, as in Central America, weak possessive adjectives may be preceded by the indefinite article or by otro, as in un mi amigo ‘my friend/a friend of mine’, otro mi hermano ‘another of my brothers’. This structure is probably best analysed as an archaism, in the sense that it continues a pattern that was once common in the Iberian Peninsula.

General Southern Cone items found in Paraguay include patotero ‘hooligan’, petizo ‘short’, pituco ‘snob’, bachicha ‘Italian’, batacazo ‘windfall’, canaleta ‘gutter’, chiche ‘small’, guaso ‘rude/crude’, negociado ‘shady deal’, paseandero ‘inclined to go out a lot’, rebuscársela ‘to get by (on your wits)’, retar ‘to tell off’.

Ríoplatense items that are common in Paraguayan Spanish include the following: bolilla ‘topic’, abatatarse ‘to lose one‘s nerve’, banderola ‘fanlight’, bolada ‘opportune moment’, cachada ‘joke’, corpiño ‘bra’, despachante ‘customs officer’, desprender ‘to undo (a button)’, lavandina ‘bleach’, merengue ‘mess’, muñequear ‘to pull some strings’, palenque ‘tethering post’, pozo ‘pothole’, retacear ‘to be sparing with’, soquete ‘ankle sock’.

The majority of words of Guaraní origin are terms for natural kinds or cultural products: agatí ‘dragonfly’, ñahatí/ñetí ‘small mosquito’, buhú/mbutú ‘horsefly’, cama ‘udder’, había ‘thrush/blackbird’, mainunguí ‘dragonfly’, muá ‘glow-worm’, pehagüé ‘late child’, teyú/tiyú ‘iguana’, ñandutí (exquisite lace), ñandú (ostrich-like flightless bird), urubú ‘vulture/buzzard’. Two very common guaranismos are mitaí ‘child’ and karaí (instead of señor).