Spanish in the Canary Islands

1. Introduction

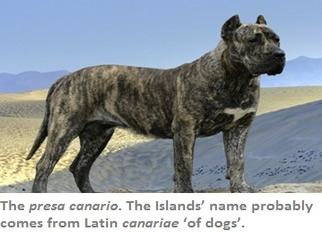

The conquest of the Canary Islands marks the beginning of the Atlantic expansion of the Castilian state. The first phase in the incorporation of the Islands to the Crown of Castile is known as the Conquista Betancuriana (1402–5) and was led by Jean de Béthencourt (depicted in the image on the right). Béthencourt was a Norman but in this enterprise he represented the Castilian monarch Enrique III, el Doliente. The Conquista Betancuriana involved the subjugation of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and El Hierro. These territories, together with La Gomera were subsequently appropriated by Castilian nobles through purchase and marriage, during the phase known as the Conquista señorial castellana, which lasted until 1450. A final phase, the Conquista realenga (1478–96), carried out directly by the Crown of Castile, extended the conquest to Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife.

Andalusians appear to have had a pre-eminent role in both the subjugation of the Islands (including the elimination of the native Guanche population) and the establishment of the new civic, religious and political apparatus. In his account of the colonization of the Canaries, Aznar Vallejo (1986:206–7) writes that:

[...] la retaguardia de la colonización estaba establecida en los puertos de la Baja Andalucía, de donde procedían la mayoría del clero y los titulares del señorío de las islas. Por otro lado, hay que señalar que la mayoría de la población «flotante» era igualmente andaluza, tanto mercaderes como marinos.

‘The rearguard of the colonization was based in the southern Andalusian ports, which supplied the majority of the Islands’ clergy and land-owning class. In addition, it should be noted that the majority of the “transient” population – merchants and seamen alike – was Andalusian.’

The

connections with Andalusia continued for centuries; in particular the Canaries

were crucial stepping-stones on the flotilla routes  that linked Andalusian

ports to the Caribbean. Not surprisingly, then, Canary Island Spanish has

developed along very similar lines to Andalusian Spanish. Indeed, together with Andalusian Spanish and Caribbean Spanish, it belongs to the general variety known as Atlantic Spanish.

that linked Andalusian

ports to the Caribbean. Not surprisingly, then, Canary Island Spanish has

developed along very similar lines to Andalusian Spanish. Indeed, together with Andalusian Spanish and Caribbean Spanish, it belongs to the general variety known as Atlantic Spanish.

2.

Phonetics and phonology

As in much of Andalusia, seseo is the norm, although isolated pockets of ceceo may persist in rural areas.

Canary speech coincides with Andalusian Spanish also in its strong tendency towards consonantal weakening. Thus [x] → [h] modification is routine and syllable-final /s/ undergoes the processes just outlined for Andalusian Spanish.

The liquids

too may be subject, in syllable-final position, to some of the pressures

described in the section on Andalusian Spanish. Thus fieldworkers report cases

of /l/ being realized as [ɾ] and vice versa (e.g. [aɾkiˈle] alquiler ‘rent’, [fulɣoˈneta] furgoneta ‘van’), semivocalization (e.g. [ejˈkwejpo] el

cuerpo ‘the body’), assimilation (e.g. [ˈkanne] carne ‘meat’), and elision (e.g. [koˈme] comer ‘to eat’).

Finally, [h] may be retained as a reflex of

Latin word-initial or post-prefixl /f/ in rural speech and the

lower sociolects. For example, [ahoˈɣaɾ] ahogar

3. Syntax

and Morphology

As in northern Castile, the preterite is often

used where speakers from the central and southern Peninsulawould use the

perfect; thus, for example, Vine hoy ‘I arrived today’, ¿Te caíste, mi niño? ‘Did you fall over, child?’, ¿Dónde

estuvieron? ‘Where have you been?’.

It is not uncommon for subject pronouns to be

placed before an infinitive, instead of after, as in standard Spanish: para ellos entender ‘for them to

understand’. This type of word order is common also in the

Caribbean, an area noted for its historical and commercial links with the

Canary Islands.

Older speakers may exhibit non-inverted wh-questions when the subject NP is a pronoun: ¿Qué tú dices? ‘What do you say?’.

Finally, as in Andalusian Spanish, ustedes is used in place of Castilian vosotros/-as.

4.

Lexicon

Only a handful of Guanche items survive in the

Canary lexicon. Examples include gofio ‘toasted maize’ (shown here on the right), gánigo ‘bowl’, baifo ‘baby goat’ and ténique (= one of three stones used to make a traditional fire for cooking).

More abundant are words of Latin American origin, which is unsurprising given the long tradition of Canary emigrants to

the Caribbean returning to their homeland: guagua ‘bus’ (Caribbean), atorrarse ‘crouch down’, machango ‘idiot’ (Cuba), rasca ‘drunkenness’ (Venezuela), cucuyo ‘firefly/glow-worm’ (Ecuador, Puerto Rico, Domincan Republic, Uruguay and Venezuela), fañoso ‘having a nasal pronunciation’ (Caribbean, Venezuela).

There are also quite a few words of western Iberian

origin, i.e. Lusisms and items from Galician: fechar (from Portuguese fechar) ‘to close’, andoriña (from Galician) ‘barn swallow’, garuja (from dialectal Portuguese caruja) ‘fog/drizzle’.

Finally, it is important to note that a number of originally nautical or maritime words have acquired an additional everyday sense in Canary Spanish. For example, jalarse comes from Old Spanish halar ‘pull [a rope, an oar etc.]’ but in Canary Spanish it can be used with the meaning ‘eat up’, as in the example below (from the on-line dictionary of the Academia Canaria de la Lengua, http://www.academiacanarialengua.org/).

Cuando llegó del trabajo, se jaló una taza de leche de cabra con gofio.

‘When he got home from work he bolted down a cup of goat’s milk with gofio.’

Similarly, liña (no longer used in the Iberian Peninsula) originally referred to a fishing line or to a sounding line, but in Canary Spanish it can be used to refer to a washing line.

References

Aznar Vallejo, Eduardo. 1986. ‘La colonización de las Islas Canarias en el siglo XV.’ In En la España medieval, Tomo V (Madrid: Universidad Complutense), pp 195–217.