(1) Vos sos por naturaleza violento y peleador, no lleves el arma.

‘You are by nature violent and quarrelsome – don’t carry the weapon.’

(Jorge Halperín, in ABC; retrieved using Corpus del Español)

The equivalent of vos sos in the Iberian Peninsula would be tú eres.

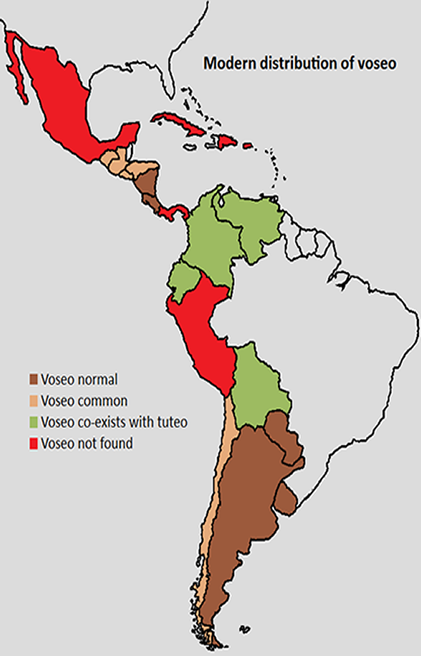

From the Peninsular perspective, voseo represents an archaism, in that it involves the retention of a pronoun and verb forms that have died out in Europe. In Latin America, however, voseo is very much alive, belonging to the speech of about forty percent of Spanish speakers in the region. As can be seen from the map below, it is associated above all with the River Plate area, and in particular Argentina, but it also enjoys a good deal of vitality in Central America, Chile and parts of the Andean region.

2. Historical origin

2.1 Old Spanish

Old Spanish inherited the second-person pronouns tu (singular) and vos (plural) from Latin. In Classical Latin, deference towards an addressee was not formally marked in the pronominal system. However, it seems likely that in later varieties the practice evolved of using the plural form vos with singular reference either in formal contexts or to acknowledge the superior social status of the addressee.

This practice must have been extended and consolidated in Ibero-Romance, because by the Old Spanish period vos clearly has the function of a singular deferential term of address. In the twelfth-century epic Poema de Mio Cid, for example, the Cid entrusts his standard to the knight Pero Bermúdez using the following language:

(2) E vos, Pero Vermuez, la mi seña tomad

‘And you, Pero Bermúdez, take my insignia’

(Poema de Mio Cid, line 689)

The Old Spanish familiar second-person singular subject pronoun was tu, exactly as in modern Spanish (modulo the absence of an acute accent above the letter u), while the deferential category was unmarked in the plural. Overall, then, the medieval Spanish system of second-person pronouns was as in Table 1 below, from which it can be seen that the system was structurally identical to the one found in modern French.

Familiar |

Deferential |

|

|---|---|---|

Singular |

tu |

vos |

Plural |

vos |

|

(3) Señor, ¿qué es lo que vuestra merced manda?

‘Sir, what is it that you require?’

(Miguel de Cervantes, Entremeses, 1582; retrieved using Corpus del Español)

This newer deferential term of address also had plural form, namely vuestras mercedes, implying that for the first time in the history of Spanish the deferential ~ familiar distinction came to be formally marked in the plural.

Taking all of the foregoing changes into account, the system of terms of address that existed at the outset of Spain’s overseas expansion to the Americas can be idealized as in Table 2 below.

Familiar |

Deferential |

|

|---|---|---|

Singular |

tu ~ vos |

vuestra merced |

Plural |

vos | vuestras mercedes |

Aquí viérades a la gente vil y a los azotados y desorejados en Castilla y desterrados para acá por homicianos y homicidas, y que estaban por sus delitos para los justiciar, tener a los reyes y señores naturales por vasallos y por más que bajos y viles criados (Historia de las India, libro II, cap. I)

(‘Here you must see how commoners, criminals and miscreants deported from Spain as killers and murderers, and who would have had to pay for their crimes had they remained, treat the native kings and leaders as vassals and as worse than lowly or common servants.’)

Given this combination of group solidarity and a heightened sense of self-worth which seems to have characterised early colonial society, it would not be unexpected for a pronoun like vos, with its residual deferential value, to continue to be used even as it fell out of use in metropolitan Spain.

Whatever the exact causes, vos came to be the usual pronoun by means of which much of the white criollo population addressed one another, except in contexts in which a clear indication of deference was required, in which case the formula vuestra merced was used. Singular vos thus remained an integral part of the colonial dialect, in many areas outcompeting and ultimately displacing tú. Importantly, however, the colonial affinity for vos was kept in check or even reversed in those areas that maintained strong links with Spain, notably the Caribbean (due to its role as a hub for shipping), the viceregal capitals of Mexico City and Lima and major population centres along the Andean spine and the Pacific Coast, a fact which goes a long way towards accounting for the relatively peripheral location of the principal voseante areas in the former Spanish colonies.

It should also be noted that in some of these strongly voseante areas – notably Argentina – the triumph of vos over tú did not occur until the nineteenth or early twentieth century (see e.g. Fontanella de Weinberg 1987). This may perhaps be related to the rise of nationalist sentiment that accompanied the movement for independence from Spain. Conversely, in Chile, use of the pronoun tú appears to have been partially reintroduced as a consequence of the normative efforts of nineteenth-century grammarians such as Andrés Bello and a school system that has traditionally been Peninsula-centric in linguistic matters.

The plural form ustedes does not represent a contraction of vuestras mercedes, but is instead an analogical innovation created by applying the plural suffix -es to usted. For reasons that are not entirely clear, in those areas where vosotros never took root, ustedes came to be used as an unmarked plural term of address. Thus in Latin American, Canary and Andalusian Spanish it is now used indiscriminately in contexts in which Castilian Spanish requires ustedes and those in which Castilian Spanish requires vosotros.

3. Associated verbal morphology

Vos is normally used with verb forms that descend from the Old Spanish second-person plural forms, which reflects the pronoun’s originally plural value in terms of number.

3.1 Declarative verb forms

Except in the preterite and the imperative, the endings of the Old Spanish

second-person plural consisted of the conjugation vowel (a, e, or

i) followed by the suffix -des, as in fablades ‘you speak’,

fazedes ‘you do’, and dezides ‘you say’ (corresponding to

habláis, hacéis and decís respectively in the modern language).

The intervocalic -d- in these endings was pronounced as a weak fricative

[ð] and was gradually lost through lenition. This weakening occurred first,

during the fifteenth century, in paroxytone forms (those stressed on the

penultimate syllable) and later, in the seventeenth century, in proparoxytone

forms (stressed on the antepenultimate syllable). For instance, fablades

(present indicative) evolved from [haˈβlaðes] to

[haˈβlaes], while the imperfect form

fablavades [haˈβlaβaðes] developed into

[aˈβlaβaes] about two centuries later. (Note that Old Spanish f was pronounced as [h] when it occurred before /a/, and although it is now actually written as h, this h is unpronounced.)

The loss of intervocalic -d- created a hiatus, which Spanish subsequently

resolved—consistent with its general historical pattern—through further sound change.

In this case, the repair produced two distinct patterns of endings, known as the

dissimiliated (diphthongizing) and assimilated (monophthongizing) types.

In the dissimiliated type, the second vowel of the hiatus was semivocalized,

yielding [-aes] → [-ajs] and

[-ees] → [-ejs]. This process is termed

dissimilation because the second vowel becomes less like the first, thereby

eliminating the hiatus by forming a diphthong.

In the assimilated type, the second vowel in the hiatus became identical to the

first and was absorbed by it, producing [-aes] →

-as, [-ees] → -es, and

[-ies] → -is. In Peninsular Spanish, these

assimilated endings disappeared in the -ar and -er conjugations but

survived in -ir verbs, where the dissimilated forms never developed. In most Latin

American varieties that retain vos, however, the assimilated endings

persisted and were reinterpreted with singular meaning.

A significant structural consequence of this historical process was the

merger of second-person plural and singular forms in several tenses where

the original plural was proparoxytone—most notably the imperfect, conditional and

imperfect subjunctive. Thus, modern forms such as cantabas could derive

either from plural cantavades (after -d- loss and vowel assimilation)

or directly from singular cantavas. As a result, voseo and tuteo forms are

identical in these tenses: vos/tú hablabas ‘you used to speak’,

vos/tú hablarías ‘you would speak’, and

para que vos/tú hablaras ‘so that you might speak’.

A comparable merger occurs in monosyllabic verbs of the present indicative, such as

das ‘you give’ and has ‘you have (aux.)’, which could derive

from either plural dades, habedes or singular das,

has. The verb ser is exceptional, since its inherited singular

eres (< Latin eris) contrasts with the assimilated plural

sos (< Old Spanish sodes), yielding the modern opposition

tú eres vs. vos sos.

Table 3 lists the assimilated vos-related verb endings found in Latin America, which vary according to region.

The Old Spanish forms from which the modern ones derive are shown in parentheses beneath each entry,

and the syllable that originally bore the stress is highlighted in bold.

| -ar |

-er |

-ir |

|

Present indicative |

cantás (cantades) |

comés (comedes) |

vivís (vivides) |

Present subjunctive |

cantés (cantedes) |

comás (comades) |

vivás (vivades) |

Imperfect |

cantabas (cantavades) |

comías (comiades) |

vivías (viviades) |

Imperfect subjunctive |

cantaras (cantarades) |

comieras (comierades) |

vivieras (vivierades) |

Imperfect subjunctive |

cantases (cantassedes) |

comieses (comiessedes) |

vivieses (viviessedes) |

Future |

cantarés (cantaredes) |

comerés (comeredes) |

vivirés (viviredes) |

Conditional |

cantarías (cantariades) |

comerías (comeriades) |

vivirías (viviriades) |

4. Associated clitic and possessive

In modern Spanish, the clitic or weak

pronoun and the possessive adjective that go with vos

are the same ones that go with tú (see examples

(4) and (5) below), but vos occurs as

the object of a preposition (see example (6)):

(4) ¿Te acordás de mí?

‘Do you remember me?‘

(5) ¿Vos creés que en tu casa no se habrán dado cuenta?

‘Do

you think that in your house they won’t have realized?’

(6) Claro, como todos viven pendientes de vos.

‘Of course, as

everyone’s life centres around you.’

This state of affairs was not always the case. In Old Spanish, the weak pronoun corresponding to the subject pronoun vos was unstressed vos, which over time lost its initial consonant, surviving as os, while the corresponding possessive was vuestro, both items now being used exclusively with vosotros.The formation of the paradigm vos, te, tu(yo) dates from about the eighteenth century and was much decried by nineteenth-century normative grammarians such as Andrés Bello.

References

Covarrubias, Sebastián de. 1611. Tesoro de lengua castellana o española. Ed. by Martín de Riquer (1943). Barcelona: S.A. Horta.

Fontanella de Weinberg, Beatriz. 1987 El español bonaerense. Cuatro siglos de evolución lingüística (1580-1980). Buenos Aires: Hachette.

Moreno, María Cristobalina. 2002. ‘The address system in the Spanish of the Golden Age’. Journal of Pragmatics 34, 1: 15-47.

Williams, Lynn. 2004. ‘Forms of address and epistolary etiquette in the diplomatic and courtly worlds of Philip IV of Spain.’ Bulletin of Spanish Studies. 81, 1:15–36.