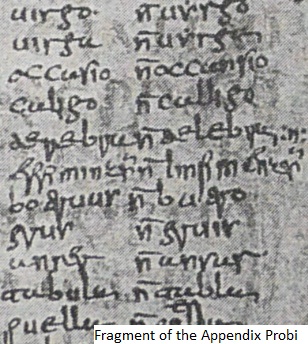

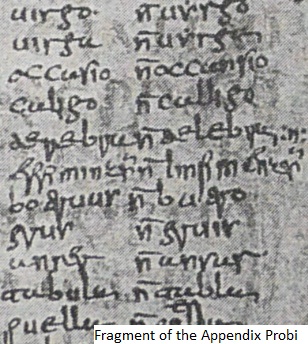

in the Appendix

Probi we find recommendations such as the following:

in the Appendix

Probi we find recommendations such as the following:1.1 Classical Latin

The Classical Latin orthography had five vowel letters, which can be transliterated as a, e, i, o and u (although there is only a partial resemblance between the latter forms and the equivalent letters in Latin handwriting or Roman cursive). Originally, each of these five vowels had both a long and a short pronunciation. Vowel length can be indicated by placing either a macron or a breve above the letter in question, as shown below, but it should be remembered that this is a practice that was developed by scholars writing about Latin rather than something that the ancient Romans did themselves.

The five Latin vowel letters each denoted a pure vowel when used individually. There were, however, three diphthongs, designated by the digraphs ae, oe and au, as in Aegyptus ‘Egypt’, foetidus ‘stinking’ and taurus ‘bull’. Originally, these diagraphs probably represented the diphthongs [aj], [oj] and [aw] respectively.ā, ē, ī, ō, ū (macron, long pronunciation)

ă, ĕ, ĭ, ŏ, ŭ (breve, short pronunciation)

| Stressed and unstressed syllables | Stressed syllables only | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulgar Latin | Classical Latin source | Vulgar Latin | Classical Latin source |

| /a/ | ā, ă | ||

| /e/ | ē, ĕ, ĭ | /ɛ/ | ĕ |

| /i/ | ī | ||

| /o/ | ō, ŏ, ŭ | /ɔ/ | ŏ |

| /u/ | ū | ||

mĕtum [ˈmεto] > [ˈmjeð̞o] miedo ‘fear’

nĕb(ŭ)lam [ˈnεbola] > [ˈnjeβla] ‘fog’

In contrast, while the [wo] diphthong survived into Italian, as is indicated by words like fuoco ‘fire’, ruota ‘wheel’ etc., it evolved to [we] in most Iberian varieties of Romance:

fŏcum [ˈɸɔko] > [ˈɸwoko] > [ˈfweɣo] fuego ‘fire’

prŏbam [ˈpɾɔba] > [ˈpɾwoβa] > [ˈpɾweβa] prueba ‘proof/evidence’

A following syllable-final nasal had the effect of slightly raising the tongue height of /ɔ/ and so a number of words containing ŏ + nasal + consonant escaped diphthongization. For example, the modern reflex of mŏntem is monte ‘mountain’, rather than *muente. Similarly, hŏm(i)nem ‘man/human’ delivers modern hombre (although huembre is sporadically attested in older forms of Spanish).

It should also be noted that the diphthong [je] (< ĕ) was sometimes reduced in Old Spanish to [i], particularly before /ʎ/ and, to a lesser extent, before syllable-final /s/. Similarly, the diphthong [we] (< ŏ) underwent occasional reduction to [e], the favoured context being after /l/ or /ɾ/:

castĕllum > Old Sp. [kasˈtjeʎo] castiello > Mod. Sp. [kasˈtiʎo] castillo ‘castle’

flŏccum > Old Sp. [ˈflweko] flueco > [ˈfleko] fleco ‘fringe’

The vowels that were capable of being affected were /a, ε, ɔ, e, o/. When affected, these raised to /e, e, o, i, u/ respectively, implying that they each raised by one degree of aperture.

The [j] which triggered the metaphony had a variety of sources, including (unstressed) front vowels that semivocalized after the loss of the hiatus and velar or lateral consonants that semivocalized in syllable-final position. In most cases the [j] did not itself survive into Old Spanish, being either elided altogether or, more commonly, absorbed into an adjacent consonant. As a general rule, the earlier the [j] disappeared the weaker its effect was in terms of causing vowels to raise. In the extreme case of the [j] that was involved in the palatalization of Latin /t/ and Latin /k/, which resulted ultimately in the creation of modern /θ/, disappearance occurred at a very early date, leaving no time for vowel raising to take place.

Metaphony did not apply uniformly across the vowel system. The vowels that were most consistently affected were /ε/ and /ɔ/, corresponding to the short vowels ĕ and ŏ in stressed syllables. The vowels that were least affected were /a/ and /e/. In the case of /a/, metaphony only seems to have occurred if the [j] was – or came to be – in the same syllable as the /a/.

Examples of vowel raising are given in Tables 2a and 2b below.

/ɔ/ > /o/ |

/o/ >

/u/ |

|---|---|

| ŏctō [ˈɔjto] > ocho ‘eight’ | plŭviam [ˈploβja]

|

| pŏdium [ˈpɔdjo] > poyo ‘stone bench’ | mŭltum [ˈmoɫto] > [ˈmojto] > mucho ‘much’ |

| fŏlia [ˈhɔlja]

|

pŭgnum [ˈpojno] > puño ‘fist’ |

| ŏstream [ˈɔstɾja] > ostra ‘oyster’ |

In addition to the foregoing changes, which affected stressed vowels, a parallel phenomenon affected /e/ and /o/ in unstressed initial syllables, with raising to /i/ and /u/ respectively:

caemĕntum [keˈmjento] > cimiento (whence cimientos ‘foundations’)

cognātum [kojˈnato] > cuñado ‘brother-in-law’

cochleāre [koˈkljaɾe] > cuchara ‘spoon’

Note also that stressed vowels were occasionally

raised under the influence of final /i/. For example, modern Spanish vine ‘I came’ is descended from Latin vēnī, a derivation which implies first of all metaphony in relation to the root vowel /e/ and, subsequently, replacement of final /-i/ by /-e/. Analogously, the imperative form vĕnī, where the root vowel is /ε/, delivers ven

4. Syncope of intertonic vowels

Intertonic or unstressed internal vowels

occupied a position of relative weakness in words and so were prime candidates

for syncope (i.e. loss). In the examples below, the syncopated vowel is underlined in the Latin etyma (as can be seen from the hostal example, loss of the intertonic vowel often triggered some readjustment of the consonant cluster produced by the syncope):

ciudad ‘city’ < cīvĭtātem

pueblo ‘people’ < pŏpŭlum

ojo ‘eye’ < ŏcŭlum

hostal ‘hotel’ < hŏspĭtāle

The only Latin intertonic vowel to survive into modern Spanish is /a/, the vowel with the highest degree of sonority (i.e. acoustic intensity). With the exception of /a/ all intertonic vowels had been lost in Spanish by the end of the Early Middle Ages, although this result was achieved in two distinct phases.

The first phase, which appears to have taken place before the end of the Latin period, was phonologically conditioned, in the sense that syncope occured only when the relevant vowel was

adjacent to /ɾ/

or /l/ or, occasionally, /s/. Thus already  in the Appendix

Probi we find recommendations such as the following:

in the Appendix

Probi we find recommendations such as the following:

speculum non speclum (> espejo ‘mirror’)

viridis non virdis (> verde ‘green’)

Subsequently, in pre-literary Spanish, there was a generalized loss of the intertonic vowel (although /a/, as noted above, was unaffected). This process played an important role in determing the phonetic shape of a large number of words. Some examples are given below:

vĭndĭcāre > vengar ‘to avenge’

līmĭtāre > lindar ‘to border’

delĭcātum > delgado ‘thin’

domĭnĭcum > domingo ‘Sunday’

mar ‘sea’ (< mare [ˈmaɾe])

pan ‘bread’ (< pānem [ˈpane])

sed ‘thirst’ (< sĭtĭm [ˈsete], later [ˈseð̞e])

hostal ‘hotel’ (< hŏspĭtāle [ospeˈtale], later [osˈtale])

mes ‘month’ (< mēnsem [ˈmense], later [ˈmese])

The other wave of apocope, associated primarily with the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, did not (in the general case) lead to any permanent change and usually involved variable or stylistic elision. This variable elision was not phonologically conditioned, as was the permanent sound change just mentioned, but occurred after almost any consonant. The example below illustrates apocope after the palato-alveolar affricate /tʃ/, the word leche being shortened to lech:

La lech e la manteca e el queso deuen uenir al uso de las monias.

‘Milk and butter and cheese should be for the use of the nuns.’

(Documentos castellanos de Alfonso X - León)

Variable elision of final /e/ in enclitic pronouns is also well attested in the written texts of the period. The example below has diol for diole:

& diol un colpe tan grand; que luego a pocos de dias fue muerto.

‘And he gave him such a blow that within a few days he died.’

(Estoria de España I)

mīlle [ˈmille] > [ˈmiʎe] > [ˈmil] mil

ĭlle [ˈelle] > [ˈeʎe] > [ˈel] él

pĕllem [ˈpεlle] > [ˈpjeʎe] > [ˈpjel] piel

The geminate lateral in these words lenited to /ʎ/, which depalatalized as a by-product of the apocope, Spanish phonotatics disallowing /ʎ/ in word-final position.