writing

The Kink in the Arc

Participation in Paul Becker's collective ekphrasis novel, The Kink in the Arc

|

_________________________________________________________________________

|

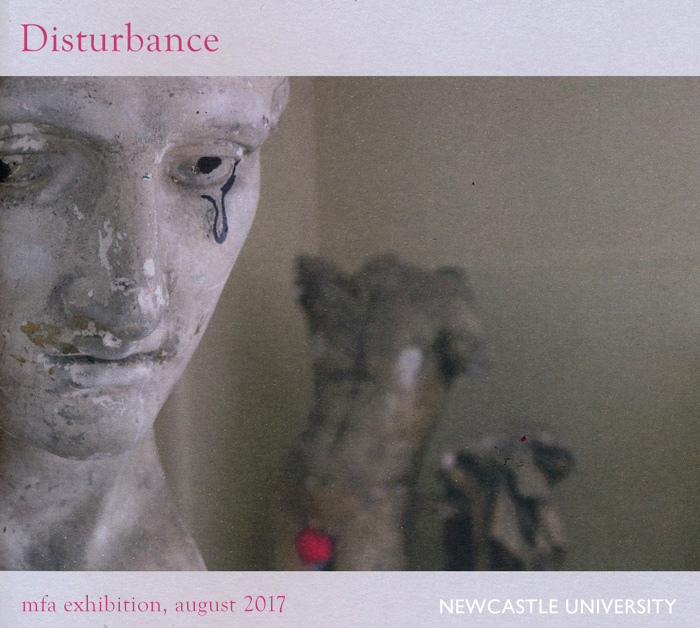

disturbance

It’s a warm, muggy summer’s day and uncommonly quiet in the building - seemingly almost shut down, cleaned out, nothing much happening, furniture sparse, studio doors closed. To knock seems an intrusion. I wander the corridors: up the stairs to the attic, down stairs to the basement, past studio doors with inspection panes papered over. I come across a notice hanging outside one room: “student working, please do not disturb”.

Such silence begs the question of whether anything is really happening that we might disturb? It also seems a kind of paradox: art schools are full of disturbance and the student, I am sure, is themself aiming to do what artists do: to disturb material, thought and feeling. Artists do this in ways that are sometimes dynamic and raucous, expending blood sweat and tears, but in hushed ways too, borne of quiet reflection, studious experiment or painstaking execution.

To enter these studios at this point, six weeks before the work is ready to meet an audience, is tantalising. I am struck by the indulgence of it: ten artists occupying single spaces normally housing many, many more. One studio sprawls chaotically like a den, another appears domestic, others are more like well-organised offices or laboratories and some have become gallery-like spaces already. In The Poetics of Space, Bachelard discusses the house; he writes that it “allows one to dream in peace”. Visiting the ten summer studios of these artists brings this to mind, for these rooms afford not only space for making but also for thinking and reflection. They provide a kind of habitat that is similar to that which Bachelard refers to as shelter and protection for the dreamer - for the reverie that plays such an essential part in the creative process.

These sometimes huge voids seem to physically swallow up the solitary chairs that furnish the rooms and to dwarf the artists themselves, but not their work which, sensing its own potential, is just beginning to meet the challenge of positively affecting the space; forming a synergy with it. As a result of this indulgent provision space becomes critical, not simply as a site of production and display but weaving its way into the work’s conceptual fabric. These artists draw their own individual spaces into quirky relationships with light, with material, form and colour; spaces are particularised as vessels for textual information and imagery; become animated by the temporal, or are ‘asked’ to form a relationship to spaces beyond.

So…behind those inscrutable closed doors, belying the quietude, much is actually going on, disturbance holds sway. Work is being produced: secrets to be well kept until the point of no return when confidence earned through endeavour trumps doubt. The work then to be handed over for its meaning to be determined by each and every one who encounters it on the occasion of its exhibition.

And it occurs to me how very different this summer phase of concentrated solitary working is to the preceding nine months (how appropriate) that paved its way. In those months this collection of individuals with their disparate backgrounds and their many different life stories, worked side by side in a shared space. They regarded one another’s practice daily, talked together, ate together, sometimes ignored one another while peering out of the corner of their eye at what their colleague had put up on the wall at the far end of the studio - registered fleetingly in order to be thought about later. It is indicative that unlike other studios in the building their communal space had no extra walls or individual cubicles erected. They kept it open-plan - open to a spirit of exchange, fostering that wonderful engine of change: conversation. This is one reason, and an important one, why some of these artists chose to return to art school, or to step inside its warm embrace for the first time after distinctly other chapters of their lives: to practice in the presence of others.

To practice in the presence of others is to be affirmed in a shared enterprise; to be influenced however indirectly, unwillingly or unknowingly; to absorb the struggles and triumphs of others as energy for oneself and one’s own practice. This is heartening but what I find compelling is its randomness: the chance collection of individual personalities, each with their own highly distinctive versions of Einstein’s stated pre-requisites: “Curiosity, obsession and dogged endurance, combined with self-critique”. This has helped generate the idiosyncrasies that have both fed their work and are its outcome; evidenced in the particularity, even the peculiarity, of each piece of work on show here and the character of each installed exhibition.

You will sense that my fascination with how work gets made is as strong as with what gets made. Since first being spell-bound many years ago by Braque’s late studio paintings I have been intrigued by the spaces and conditions in which artists make their work, hence my preoccupation with the spatial settings of these artists’ year of practice. I am particularly curious too about the other part of ‘how’: the creative process. We know that decisions that get taken for all the right reasons can be applied in all the wrong ways (and vice-versa) and still generate remarkable solutions – the unfathomable gap between an idea or plan and what happens. I am taken with what E.M. Forster implies is required to enable creativity to operate at a higher level. In his essay, Anonymity: An Inquiry, he suggests that the human mind has two personalities: an upper one which is “conscious and alert” and a lower personality which is “in many ways a perfect fool but without it there is no literature because unless a man dips a bucket down into it occasionally he cannot produce first class work”. He pays tribute to delving into “the obscure recesses of our being” as the means by which the writer, and by implication other artists, might “soar to the heights”.

That sense of the obscure, the unfathomable and mystic-like, that is essential to creativity but impossible to articulate - that is beyond words - brings me to Roland Barthes’ much quoted statement from Camera Lucida and, in turn, back to the thoughts prompted by the notice on the studio door with which I began.

“What I can name cannot really prick me.

The incapacity to name is a good symptom of disturbance”

_________________________________________________________________________

|

| stephen, ian, zoe, rita… and you... and me catalogue text: newcastle university ba degree show 2017 |

||

|

My brother, Stephen, told me that if I looked on the floor in the far corner of the painting studio now listed as 5.02, I would find the tooth-brushed spatter that fell off and around the edges of Ian’s paintings, Ian Stephenson’s. I looked and I was not disappointed; it filled me with delight. Those miniature pinheads of pigment now sit quietly beneath around thirty-five layers of flat, matt-grey degree show floor paint. Does memory serve me well? Probably, but approximately.

|

|

And Rita?

For the last few years I have shared a room in the Fine Art building with the elegant classical cast of a Roman copy of a Grecian Venus - good company. In that room there used to be a wooden storage platform situated, seemingly hanging, up near the skylight – out of reach, piled high with material, accessible only by a ladder that was never provided.

Five years ago, from the top of a set of steps, I sifted like an archaeologist through the skins of grime, the layers of dust and the strata of time on that platform. Beneath the top crust of dirt were student drawings by those whose names I knew from my first year’s of teaching, beneath were works by friends and peers from my own time as a student, and at the very depth poked Victor’s signature on a Christmas card to Kenneth, old-school style preview cards, bills and receipts from another time that seems almost ancient. Wedged in, turned to the wall, rather self-effacing, a Northern Young Contemporaries entry label neatly written by hand on its back, another student’s work - an unassuming degree show oil painting on board: Rita’s.

So Holly, that’s what Rita means to me – we each, we all, bring our histories together, our stories reach forward as well as back, we play a part. Stretching alphabetically from Aglae to Vanessa there are yet more names held elsewhere in the pages of this catalogue and on the walls of this degree show: sixty bodies of work presented for attention, scrutiny - enjoyment even; sixty sets of stories; sixty traces left in the fabric of the Fine Art building; sixty artists making their mark.

Heather, whose way with words is more nimble than mine, asks me for a few to include here. In turn, I would like to use some of hers: she asks for words from me “as the wind at our back”. I have never thought of it this way but I am taken with the metaphor. The wind at your back as, perhaps surprisingly, you have been at mine… such reciprocity - encouraging one another on.

_________________________________________________________________________

|

in others' words

catalogue introduction: newcastle university ba fine art degree show 2015

Yes… like you I find words difficult, I find finding words difficult… I was thinking about this the other night, trying to pitch in to this piece you asked me to write, when… I switched on the radio around midnight… and out of that little box of black magic these words found me… "Sam Cooke said this when told he had a beautiful voice: He said 'Well that's very kind of you, but voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth.' Think about that the next time you are listening to a singer"… and think about that when looking at a painting, tuning in to a video, navigating an installation… I couldn't have put it better myself.

Sam Cooke sang of falling in love. Like falling in love, art is a disturbance of what is; a reordering of existing material; an encounter with otherness; and a baffled certainty that what is happening – long or short, brief or lasting – has to happen. Creativity in all its forms is a passionate engagement with making something happen. The happening of art renews, replaces or renames the tired old clichés of the obvious.

I am on a roll now, in my stride, words flowing, pen to paper… but… yes, of course you guessed… I am not writing this down, I am reading it out; words tipped from the Sunday morning papers, words clearer and more to the point than mine could ever be. Turn the page, there's more… listen to this, she goes on…

...visual artists do the looking on our behalf in the same way as religious orders used to pray on our behalf. The looking of the artist’s eye creates an object that we in turn pay attention to, because we know you have to look at art. Paying attention in this way both relaxes and stimulates the brain. It hardly matters whether or not you “like” the object in question. Concentration, engagement, the thinking and discussing that follow, lift us out of a mode of being that is purely instrumental. Art galleries are places to stand and stare; places to be human – to be curious…

Any other parting shots before you go?

Well…I've enjoyed our conversations in this paradise you need to leave - stay in touch, take care, continue to explore your thoughts. You say you were not taught anything: well Grasshopper, with all that you have achieved, and to feel this way, I know our work is done. Finally, do you remember the quote I gave you soon after you arrived? "What you forget goes into the compost of the imagination". No, of course you don't…

With apologies to Bob Dylan(1), Jeanette Winterson(2), Howard Wilkinson(3) & Graham Greene(4)

(1) Speaking about the creative process of songwriting at the MusiCares Person of the Year gala, the Grammys, 6th February 2015

(2) Writing on art and the function of galleries in response to the reopening of the refurbished Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 'On the transforming power of art', The Guardian 14th February 2015

(3) In an interview to the Guardian in the 1990's, the manager of the last Leeds FC team to win the league title likened his coaching philosophy to that of an unnamed Zen master who felt he was successful only if his pupils achieved enlightenment whist unaware of ever having been taught

(4) Accounts vary but the full quote, from an interview with the writer, is believed to be "All good novelists have bad memories. What you remember comes out as journalism; what you forget goes into the compost of the imagination"

Click on images for credits

8th march 2015

_________________________________________________________________________

|

hares in the open

catalogue introduction: newcastle university ba fine art degree show 2013

It's hard - you start with this enjoyment of drawing or painting, of making things, it gives you something back, you are not sure exactly what, but if feels good. And then... then others begin to take an interest, they like what you are doing, tell you that you are "talented", and though you do not want to trust it too far that makes you feel good too - and on that warm wave of praise, encouragement and self-belief you surf into art school... and that's where the trouble begins.

You thought you had come to be taught something and that something isn't what you expected, or even wanted - and it doesn't really seem taught, more learnt than instructed, by osmosis, picking things up as a result of your own curiosity and seemingly by chance. And the questions! The contradictions! The taking everything so seriously - give me a break, can't we just relax a little, this is supposed to be enjoyable...isn't it?

The journey taken, the path travelled, by students on a course such as ours is not always easy and certainly does not fit the commonly held view of studying art as simply indulging in what comes naturally. So, in recognising this group of student's success - their ambitious, resolute-seeming, inventive, quirky work, so assured, that brooks no quarter - let's also celebrate the failures, hesitancies, headaches, doubts and desperate confusions that have made it possible!

The so called punk svengali Malcolm Maclaren said that art school taught him "that to create anything you had to believe in failure, simply because you had to be prepared to go through an idea without any fear. Failure, you learned, to be a wonderful thing. It allowed you to get up in the morning and take the pillow off your head". Doubt, risk and Maclaren's "wonderful" failure invite a minor miracle into an artist's arms - that of discovering what it is we really want to work with in terms of subjects, ideas, processes, materials, information...

|

This miracle takes many different shapes and forms: creeping up on us as a series of incremental shifts in perception, thinking and making or conversely descending like a Damascene conversion; always the result of one kind of encounter or another - a conversation, something seen, heard, read, touched - encounters, unpredictable and slightly random, that are the life-blood of art schools everywhere. For some this discovery happens early, for others - even in the group of students here whose work looks so complete, so decided - it will happen late; for a few it will even happen in the time between writing this text to the copy deadline and the opening of the show six weeks later.

Once grasped firmly hold of, this shift in emphasis gives us permission and confidence to work with dreams and intuitions, with imagination as well as logic. The notion of creative imagination has rather gone out of fashion but I delight in John Berger's description of human imagination as "dreaming, like a dog in its basket, of hares in the open". This phrase, and Einstein's thought that "logic will get you from A to B, imagination will take you everywhere", seems particularly fitting when considering this year's graduating cohort - these students have chased their "hares in the open" in characteristically diverse, lively, challenging, determined and individual, even idiosyncratic, ways.

| credits, | left to right, top: |

cody sowerby,charlotte o'shea,josh wilson, azim abas, sarah illing |

bottom: |

william vinegrad, adam laing, oscar eaton, eleanor parr |

april 2013

_________________________________________________________________________

|

unheimlich: the paintings of james quin

catalogue essay for 'evidence'

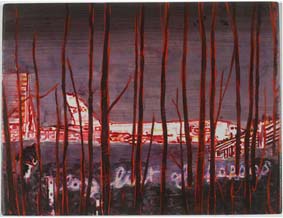

Walking down Church Street on a grey morning I glanced through the misted up window of a parked car to read across the top of a spread out tabloid: 'A WALK IN THE WOODS'. Below the headline a grainy, rather uncertain monochrome image of some banal spot was printed, the double page spread lending it some kind of importance.

|

Coming across the exact words of the title of one of James Quin's paintings in this way, just a day after visiting an exhibition of his work at the Globe Gallery last year, struck me as particularly apt. I was not so much interested in the coincidence as the way in which I felt I had stepped into Quin's shoes, that it seemed this might be just the kind of moment Quin himself would seize on as the starting point for one of his paintings. Further, that sense of finding oneself in someone else's shoes somehow chimed with the feeling I had on viewing his paintings the previous day. |

|

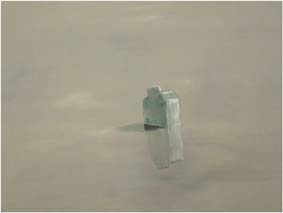

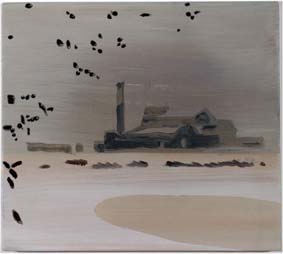

A Walk in the Woods 1 |

What struck me as I looked at those paintings was the sense they gave of being the view of a fictitious lone observer - in other words they did not seem to represent Quin's view of the world but rather that of a character he might have invented, or of an alter ego. Each painting could be said to describe a different part of the world that this solitary character inhabits, each painting a fragment of the implied narrative of his isolated existence: here he glimpses a jet plane through the trees, there he takes a walk in the wood strewn with torn remnants of clothing, he faces himself in the mirror the morning after, blank and whey faced, features bleached by a harsh stark lamp. In a studio discussion with Quin, the sculptor Phyllida Barlow put it another way: Quin paints “other people's experiences”.

|

|

|

A Long List of Lapses |

Missing |

Looking at these paintings I feel I have the same relationship to them as I might to the first-person narration of a novel or short story. I feel as though I am seeing these images through another's eyes and understand something of the 'narrator' by the way he describes his world. In this sense part of the subject of the painting exists out of the picture frame. A further analogy is that of film - these paintings have characters, artificial stage sets, locations, vantage points, camera angles, close-ups and dissolves, long shots, implied narratives, and they play with the viewer’s gaze.

Another aspect of the work that intrigues me is the way that Quin subverts the familiar, converting the ordinary into the uncanny. As Freud implies in his essay on the uncanny the power of the 'unheimlich' is arrived at not by an encounter with anything strikingly odd or unknown, rather it is held within something that has a familiarity about it. Wishing to place some kind of psychological distance between himself and his subject matter Quin begins with second or third-hand material that belongs to a common popular consciousness: he works with mug-shots of missing people from the Big Issue, photographs from the kind of news stories we read on a daily basis, star studded night skies we have all gazed at or, as in Quin's Middle Europe, overused images we cannot help but recognize. That the images have already been mediated by photography also provides a sense of familiarity - we know the type of image they are. The reference to photography also implies an element of reality or truth to the facts and, as Freud states, the play between reality and unreality is at the centre of notions of the uncanny: “He (the writer) deceives us by promising to give us the sober truth and then after all steps all over it.”

Middle Europe

Quin disturbs the familiarity he has established in subtle and unsettling ways so that by the time a painting is resolved it will have a resonance far beyond its initial source. Our encounter with one of Quin's paintings might start with a flash of recognition but we will gradually be apprehended by what is out of kilter in it and it is that quality that holds our attention and which is the real content of the work. This quality is usually one of uneasy or disquieting mystery: why is the 747 in A Long List of Lapses being observed from a hiding place behind the trees? Is the blank-faced man peering out of Missing the observer himself, caught in reflection, or his quarry? Why is the boardroom in the most recent work being entered at night by torchlight? How is it that one image makes us think of another?

In addition to the way Quin places the viewer other devices contribute to the creation of this tension. At the Globe Gallery he installed paintings in such a way that they ‘spoke’ to one another: one painting lending a particular charge to another by physical proximity or by a shared image or setting. Quin also has the knack of working his images so that they accrue resonance by their links to those we know from other artists. In conversation he has described how the painting, Better Late than Never, with its figures isolated in a muted, barren landscape had its genesis in a recent photograph of ice skaters in Suffolk. However, what determined the choice of image and the way he subsequently painted it, was the connection he found in it to Breughel which in turn triggered Quin's memory of the sequence in Tarkovsky's Solaris where footage of Kelvin and Hari's weight-lessness is cross cut with slow pans across Breughels The Hunters in the Snow. It is almost as though Quin's interest mirrors that of appositely named Quinn in Paul Auster's City of Glass: “Quinn knew nothing about crime. Whatever he knew about these things, he had learned from books, films and the newspapers. He did not, however consider this to be a handicap. What interested him about the stories he wrote was not their relationship to the world but their relation to other stories.”

I have not yet remarked on how Quin marries his interest in imagery, narrative and fictional conceits with the activity of painting but, for me, what Quin does with paint is pivotal. The way he paints tell us that crucial bit more about the person observing these scenes; it is what allows Quin to go beyond the vernacular, to convert the opportunities that the source imagery provides.

|

|

|

Missing |

The Place to Which I Sometimes Return (detail) |

In the act of painting Quin is a man in a hurry; the top layer is painted in one session, achieved fast, and tipped off the end of the brush. One brush load is sometimes sufficient to achieve an image. This reinforces the sense that permeates much of the work of rapid, furtive observations, hurried accounts, of voyeuristic glimpses; the shorthand of someone on the move. Yet as paintings they gain from this restless distillation because it reveals the versatility and plasticity of paint: dragged colour holds a painting together; two or three smears describe a house; the black marks which sit across the left side of Middle Europe, like careless studio spatter or a child's notation for a flock of birds, are what finally resolves and defines the painting. Choices of colour and tone set the scene, time and place as much as the iconography does. Quin's deft command of the formal elements results in seductive paintings that lure us in, we are held by their fluent ease as the imagery commences its unsettling work.

In James Quin's most recent work for the Red Box Gallery's boardroom he takes some of the interests described here into new territory but his intentions remain resolutely consistent. He dispenses with found imagery referring instead to first hand examination of the boardroom space itself. Painting is used as part of a developmental process towards the production of digital images rather than as the end product. However, the nature of Quin's examination of it lends the images he creates a psychological distance that is familiar from the earlier paintings. His interest in the position of the viewer is also |

|

|

re-worked: as we consider the digital images installed on the walls and computer monitor of the boardroom there is a gradual, slightly disorientating recognition that we are standing in the very space that is depicted. Reality and fiction become part of each other echoing Bachelard's observation on an extract from William Goyen's novel House of Breath that “in a passage like this, imagination, memory and perception exchange functions. The image is created through the co-operation of real and unreal”.

march 2005 |

||

_________________________________________________________________________

|

||

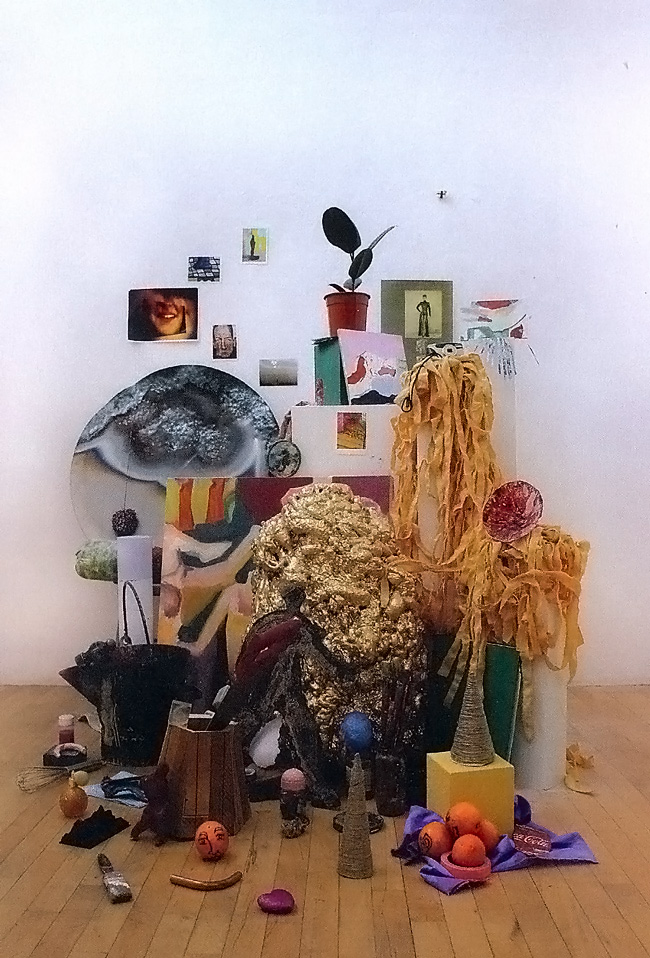

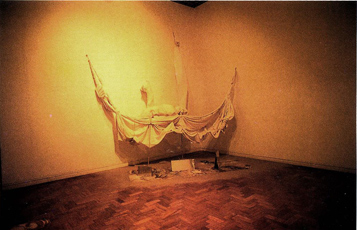

(e)scape: smitha cariappa

catalogue essay

Smitha Cariappa has titled her installation in the Hatton Gallery, Newcastle, (E)scape. What, first of all, should we make of this title? It suggests, of course, an escape: a movement - a journey - from one state to another, of liberation from confines. In addition it seems to refer to a desire to describe the features of a space - and that space might be both real and psychological: we use the word 'landscape' to define the features of a land area, 'mindscape' is used to give a sense of the mapping of thoughts. In Smitha Cariappa's room of disparate material and myriad forms, of flotsam and jetsam, we are invited to negotiate the features of her displacement, her journey, her (e)scape.

A literal interpretation might lead us to concentrate on the nature of the artist's residency from which this work has arisen: an artist from Bangalore on her first visit to Europe, her first move away from her homeland. We might assume a relinquishing of restrictions, concentrate on the word 'escape'. Yet I would rather emphasise the notion of the journey, the shift in environment and surrounding - liberating in its way but imposing other, different, but productive limitations. The fixed time-span of the artists's time in England, for example, prompting her to accept provisional solutions, benefiting from their inherent energy, rawness and direct voice. There is an evident eagerness to embrace the new surroundings - new sensations - unfamiliar impulses.

A journey can also imply a subsequent return home and (E)scape has about it the air of an artist collecting for the future, registering thoughts quickly to play with later, reviewing the contents of the bag which she will take home with her. We notice the elements of the installation just as Cariappa first noticed the sources from which they derive: objects / material from her new environment - from the market, the quayside, the Northumbrian seascape. We become curious, as she did, we skip from one element to another, we return back and forth, we make connections: the parts begin to form a whole.

Cariappa's interest in her general surroundings, in the environment - the earthscape - is also evident: we see it in her remoulding, recycling, transformation of banal material or rudimentary left-overs into something potent and valued. She acknowledges the worth in the seemingly worthless, recognises inherent values and qualities.

So, what do we find in this room? We find movements in all directions, many journeys rather than a single route from entrance to exit. We can travel, as if along a ribbon, through the three dimensions of the space; our eyes are taken up to hanging sails of canvas and rope, we enjoy a meander around scrolls of shoulder high corrugated card, we peer over them to discover small sand heaps hidden in their maze. Forms achieved through the conjunctions and manipulations of diverse material might start at the centre of the room and, as it were, stretch out across the floor to lean against a wall, or to huddle in a corner. We take it all in as if travelling through a kind of three-dimensional sketchbook. Forms are captured, some are played with, compelling juxtapositions are made: canvas knots and billows hang their neutral colours just out of reach of the washed out synthetic oranges and blues of smaller found objects camped out against an end wall. |

|

And within it all the recurring note which links these journeys and which emphasises the displacement: small drawn images, often of the human form (hands, faces, legs) are placed amongst the strewn elements of the space; sometimes hidden quietly away, one or two half-buried in sand. These figural images confirm the sense of a universal human presence in the space. They go further however: their eastern iconography and characteristics sit slightly at odds with the sculptural elements of the installation creating a tension, a strangeness, a potent 'out of placeness' which is the key feature of Cariappa's (E)scape.

july 1998

_________________________________________________________________________

|

siân bowen: paintings, drawings & watercolours

catalogue essay for 'far east-north east'

Our knowledge of an artist’s background and experience most usually, and helpfully, informs a reading and understanding of their work – occasionally too it can muddy the water, leading us to hasty conclusions a little at odds with the artist’s intentions and the content of their work. Siân Bowen’s recent paintings, drawings and watercolours present a case in point: from our knowledge that she has recently returned to this country after four years living and painting in Japan we might presume that the artfulness, clarity of design and unashamed grace of her work lies in some influence brought back with her from the East. In truth, such qualities, as well as her liking for calligraphic gestures on a sparse ground, were present in her work well before her departure for Japan in 1985. Indeed, it was the emergence of such characteristics in her work that drew her to first look at the Chinese and Japanese sumie masters such as Sesshu, to find in their ink paintings a similar regard for the natural world; rather than sourcing an influence of style or technique she identified an empathetic approach to her chosen subject.

|

|

|

Cradled |

Fragment 1 |

Those oriental master painters interpreted nature in an excitingly loose way whilst exerting a deft and exquisite control of seemingly spontaneous means. This alliance of control and freedom as a painterly vehicle to approach the transcription of landscape has great appeal for Bowen, however, one is as likely to find catalogues of Ivon Hitchens, David Jones and Winifred Nicholson scattered in her studio as those of Oriental artists of the more distant past.

All of which is not to deny the fundamental and continuing impact that those four years in Japan have had on the development of Siân Bowen’s studio practice. What the artist gained during that period arose not only from identifying a kindred approach to the natural environment embedded in Japanese culture, but also as a result of finding herself in front of an unfamiliar landscape: she had a new, and different natural world to cast her eye upon and to explore in paint. From the window of her studio located in the countryside around Kyoto she could view a hillside of bamboo sweeping in rhythm. At the foot of those hills were rice fields – sometimes stubby, charred remains, other times full of bright green shoots semi-submerged in water, depending on the season. And the seasons change very swiftly in that part of Japan – the harsh bright light of Spring and early Summer gives which way to the sultry, sulphurous skies of the rainy season, or the sudden blushing of leaves which turn to intense shades of red and rust within a week in November.

In the face of these new-found natural phenomena Bowen’s watercolours in particular were liberated: equivalents to what she could see in the landscape that surrounded her were found in a host of fresh and unfamiliar colours, a more varied and surprising family of motifs, a broader range of marks and the exploration of new ideas for compositional structure. In turn, the watercolours were instrumental in the development of a new approach to large paintings in oil on canvas. All the small watercolours had been produced directly in front of the landscape in intense, reverie-like sessions of complete concentration and response. From one motif or location a series of between twenty and thirty pieces would be painted from which Bowen would select a smaller, choice group after reviewing them once back in the studio. Such a method felt somewhat unsympathetic and unmanageable when faced with canvases of five and six foot. However, Bowen found that by selecting a particular watercolour as a ‘key’ or guide for each larger canvas she was able to connect the endeavours of large and small scale working, to establish an initial formal framework for her oil paintings and to develop large work both inside the studio and out in the landscape.

|

|

|

Fragment with Seed & Husk II |

Bombay Day |

Gradually a fully realised working method emerged and the most recent paintings produced in Northumberland are its outcome. In these paintings a watercolour is chosen and its imagery of quick and loose marks is scaled up to the size of a particular canvas and meticulously and slowly reproduced, usually in subtle shifts of light-toned colour employing glazes to create nuances of surface. Bowen expresses interest in the idea of dramatically shifting the scale of intimate, informal marks and in the notion of spending a day or more re-exploring the nooks and crannies of marks from the watercolours which took just a split second to be formed. For her, this initial stage of transcribing the watercolours to a large scale in oil serves a number of strategic purposes: it provides a ‘get acquainted’ period during which the size of the canvas support is negotiated; it allows her to beginto erode the stark white ground by suggesting form and space, and to clarify questions of content and mood. The preliminary marks derived from the watercolours are regarded by Bowen as akin to the residue of nature – fossilised imprints, the dried out remains of plant life, or sand which has been blown to cover or expose natural form. They also provide an initial structure to work with, or against, when the second phase of the painting process begins.

In this second phase the canvas is worked on directly from a chosen landscape or motif from nature, in much the same way as the early smaller work on paper. The softly modulated, broad marks of the preliminary transcription from the watercolours serve sometimes as a foil or counterpoint, other times as an underpinning, to a new round of improvised and spontaneous painting. Alternate sessions of studio and location-based painting ensue until the painting achieves its definitive form.

|

|

|

Former Gardens IV |

Former Gardens I |

It is interesting to note that Bowen’s current studio in Northumberland is perched high, overlooking a small ravine. It provides a distinctive vantage point that brings to mind the semi-aerial views of some of Peter Lanyon’s work. In the foreground overgrown woodland falls steeply to a half-obscured stream the other side of which rise small, terraced gardens. These small plots of land are variously organised and cultivated, each with its own sets of shapes and structures (hence the broken blue triangle of Cooler at the Edge). These contrasts of form, the juxtaposition of organic natural structures and those arising from mankind’s imprint, the shadows of trees and buildings across the bank of gardens, the salmon pinks of the Northumbrian evening skies are all rich ingredients that find their way into paintings and drawings that can be read as intriguingly topographical landscapes.

august 1991