text: gavin robson

| from the small hours | ||

| october 1992 | ||

Commodore Perry's ships in Nagasaki harbour. The European mind see black vessels against a golden screen. Japan as a screen against which fantasy and its partner memory can be ordered. The idea of the screen in studios across the western world as a surface, flat and impenetrable to which might be attached the image of, the thought of, things familiar - a London bridge pinned to the sky like a spread fan to the painter's wall.

|

Christopher Jones' paintings begin in Japan but they are not of Japan. Only rarely does an image speak directly of his time there. Where it does - the prayer knots in Widow's Weeds - it is attached to the surface of the painting. It holds onto its place. That place is flat and high like the backdrop to a stage. Variations within a structure of unvarying elements - three horizontal divisions of a painting nine feet by seven - may hint at a space opened, into landscape or to make a shelf for a "still life", but in the end the viewer is brought back to the surface. The mind is confined against a high wall across which it may move but through which there is no going back. The invitation to approach these paintings to examine minutely the contents of small collaged elements merely confirms that we are not confronting a window on the world. There is no going back. |

|

For easy remembering one should imagine a certain order of places upon which images (phantasmata) of all those things which we wish to remember are distributed in a certain order. Thomas Aquinas |

An order of loss. In Jones' painting Rebus-Irish Passage he hints at the human order happened upon in abandoned houses. He knows of the encounter with ironic reminders of private places turned to the outside world. A fireplace, focus of human comfort, remains suspended at the end of a demolished street. A calendar hangs from a nail far above the possibility of keeping time with passing days. Only memory can re-order these fragments. The audience cannot pass up onto the stage.

|

Jones knows that if an image is worth going back for it must be sought out and disentagled from its place. Sometimes it can only be brought into consciousness encrusted with seemingly irrelevant matter, or changed beyond dreaming - a skeleton of coral. And memory plays tricks on us, offering us what we do not need or would rather forget. Old newspapers, torn and folded where the births, deaths and marriages are thrust through onto the front page. In making paintings from associations and moods it is necessary for Jones to trap them with substitutions - to trick memory by accepting the image which stands next to the one which has been mislaid or which now goes in disguise. Finding substitutions which will hold their place in a web of images gives the artist much labour. He reworks his materials over time, constantly reassessing their relationships and the effects they will have on each other should he move them to a new place. What begins as a crisis may develop into a drama. |

The necessity of substitution brings too the poignancy of the image only half-recovered. Perfection of expression proves a mirage. In the end however it is human to "make do" and Levi-Strauss' metaphor of human culture as a bricoleur, a handyman who fixes things up into only semi-useful objects is one which the artist recognises as true. And if the result achieved is flawed should we not, like the Japanese, love it the more for its imperfection?

What emerges from Jones' paintings is the power of the urge to make a place for memories, to find an order in what is fragmentary and fading - an art of memory. He makes a screen on which to pin his past.

It often happens that a man cannot recall at the moment, but can search for what he wants and find it. This occurs when man initiates many impulses until at last he initiates that which the object of his search will follow. For remembering really depends upon the potential existence of the stimulating cause...For this reason some use places for the purpose of recollecting. The reason for this is that men pass rapidly from one step to next: for instance from milk to white, from white to air, from air to damp: after which one recollects autumn, supposing that one is trying to recollect that season. Aristotle |

______________________________________________________________________________

text: gavin robson

remaking the past

may 2007

|

Something has to be forgotten which we then get access to by revision. Remembering at any given moment, is a process of redescription; the echo can be different each time. The past is in the remaking. Remembering is a prospective project. |

|

Adam Phillip Freud and the Uses of Forgetting |

The desire to understand change in an artist's work as progressive too often leads to a false view of how he might imagine his own history. Rationalising change as framed in what are, significantly, called periods gives rise to the notion of a series of abandonings - of putting aside something exhausted and played out. The reality, in the mental life of many artists, is that the boundaries between phases of work are highly permeable. As in old houses where a suite of rooms is joined by aligned doors the contents of the past, temporarily invisible are always available if remembered in the right order.

This availability provides opportunities for the artist to behave in a way which contradicts the normal forward direction of historical narratives by re-performing a work, or a set of works, from his past. Accounts of this phenomenon frequently sound a note of embarrassment, as if the artist has proved inadequate to the task of making progress. For the artist however, such an act or re-imagining can be enormously productive. Time spent forgetting is time spent in the service of creative remembering.

It was fifteen years before Delacroix had sufficiently forgotten his early masterpiece, Algerian Women in Their Apartment, to be able to produce the magical variant now in the Musée Fabre in Montpellier. This radical reworking depended crucially on the achievement of distance. It is well known that Delacroix regarded his experience of North Africa as a way of getting back to the classical world, a world which could only be revitalised by being remembered differently. It was however two years before his memories of Morocco and Algiers had faded into alignment with the purpose. To arrive at the Montpellier painting it was necessary for him to variously forget his deep cultural inheritance, his contact through naturalism with exotic imagery and his first developed synthesis of both.

Christopher Jones' recent work touches on many similar themes. They are rooted in his contacts with Japan but depend, equally, on a measure of forgetting. To remember productively he has employed the idea of erasure, of the disappearance of the inessential in order to find a new ordering of the image.

The titles of the work which Jones produced between 1990 and 1992, after his return from living and working in Japan for two years, contained echoes of the idea of displacement. Titles such as Exile and Memoir referred explicitly to a sense of being out of place but more suggestively he grouped them all as being From The Small Hours. This sense of being in the wrong time or of being out of time returns with the present body of work produced after revisiting Japan after an absence of eighteen years.

|

As if to underscore the difficulties of remembering, Jones discovered when attempting to refind the apartment block where he had lived on the rural outskirts of Kyoto that it had been demolished. Its erasure was so complete that he found himself casting around the perimeter of the site for traces of anything he might remember. This experience seemed to him on reflection to be linked to the necessity of losing something in order to find it again through a process of creative elaboration. He began to restage elements from his earlier works and photographs of these reconstructions appear in conjunction with motifs from the work of the 1980s photographed and overpainted. It seems also as if in trying to make sense of memory it was necessary to rebuild the site from which images might come to light. |

Come to light too in that the new work has an openness and airiness, a fragility which might be associated with new growth. It may not be too fanciful to see a connection to Jones' images, based on digital photographs, of rice growing on the cleared demolition site which he encountered where his apartment had been.

|

The idea that art emerges from clearing away the accretions of cultural baggage is one which is frequently encountered in art since the late eighteenth century. Artists have taken erasure and renewal to be essential counterparts in a quest for authenticity. Very often the desire for distance from seemingly exhausted traditions has expressed itself through reaching out to the exotic construed as the primitive. Jones' view of the uses of Japanese culture is in no way however formed on the model of exoticism. He hints rather at the essential emptiness which often accompanies our encounters with foreignness, the feeling that we need to supply our own contents to flesh out the reality of the encounter. It is from sensing the paradox that the centre of these meetings is often void, that he can find a place for images from his own past. |

How those images should be manifested, and what structures will release their new, or perhaps recovered, meanings is crucial for Jones. The use of over painting is one way in which potential can be released and, as importantly, old material reabsorbed. The sensuousness which characterises the layerings of paint in some of Jones' works, and which contrasts with the austerity of the photographic base, suggests a way of recontacting primary experiences of touch and taste which lie dormant in memory.

In those pieces where etchings and monoprints are digitally enlarged the process of enlargement gives a similar impression of fatness and fullness to marks which at their true scale might seem dry and skeletal. In both cases there is a springing up from the originating image in what could be seen as a metaphor of refreshment. |

|

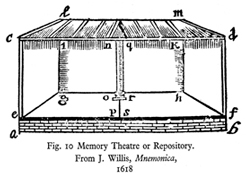

An additional point of reference on his return to Japan was the text of Frances Yates' The Art of Memory. Yates describes in detail the structures used in the ancient world by which memory can be retained and projected. These structures are for the most part based on the notion of harbouring and storing key images in an imagined architecture. Intriguingly Jones describes the possibility of producing a body of work where these structures are overtly employed and in his recent work there are hints of how this might happen.

|

|

|

The placement of key images within a field and their relationship to each other is clearly of particular importance to Jones. While the manner of their being associated depends on what might be described as a collage method there is a precision and an aptness in the way in which they are brought together which is far from the pure psychic automatism advocated by the surrealists. The ordering of images with such exactness supports a reading close to the memory training techniques described by Yates. The proposal of an architecture to locate memory, and more particularly an architecture of the theatre, hints at the possibility that images might not simply be found where they had been deposited but that they might be rendered eloquent in ways which go beyond the straightforward function of recovery.

How we imagine the theatre can come to be rather how we imagine the studio. It is in the studio that the artist instigates those conversations that animate the process of working towards resolution. He does so, even half-expects answers, believing that images can be made articulate by drawing them into relationships where they are compelled to exchange meanings - image addressing image across an empty stage.

…a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its afterlife. For a translation comes later than the original… |

Walter Benjamin The Task of the Translator |